Space engineering

SpaceWire – Links, nodes, routers and networks

Foreword

This Standard is one of the series of ECSS Standards intended to be applied together for the management, engineering and product assurance in space projects and applications. ECSS is a cooperative effort of the European Space Agency, national space agencies and European industry associations for the purpose of developing and maintaining common standards. Requirements in this Standard are defined in terms of what shall be accomplished, rather than in terms of how to organize and perform the necessary work. This allows existing organizational structures and methods to be applied where they are effective, and for the structures and methods to evolve as necessary without rewriting the standards.

This Standard has been prepared by the ECSS E-ST-50-12C Working Group, reviewed by the ECSS Executive Secretariat and approved by the ECSS Technical Authority.

Disclaimer

ECSS does not provide any warranty whatsoever, whether expressed, implied, or statutory, including, but not limited to, any warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose or any warranty that the contents of the item are error-free. In no respect shall ECSS incur any liability for any damages, including, but not limited to, direct, indirect, special, or consequential damages arising out of, resulting from, or in any way connected to the use of this Standard, whether or not based upon warranty, business agreement, tort, or otherwise; whether or not injury was sustained by persons or property or otherwise; and whether or not loss was sustained from, or arose out of, the results of, the item, or any services that may be provided by ECSS.

The implementation of this Standard can touch on intellectual property covered by patent rights. ECSS is not responsible for identifying all the patents involving a license to implement the SpaceWire Standard. Furthermore, ECSS and ESA are not responsible for ensuring the existence or legal validity of any patent related to the SpaceWire Standard.

Published by: ESA Requirements and Standards Division

ESTEC, ,

2200 AG Noordwijk

The

Copyright: 2008 © by the European Space Agency for the members of ECSS

Change log

|

ECSS-E-50-12A

|

First issue

|

|

ECSS-E-50-12B

|

Never issued

|

|

ECSS-E-ST-50-12C

|

Second issue.

|

Introduction

General

SpaceWire technology has grown organically from the needs of onboard processing applications. This Standard provides a formal basis for the exploitation of SpaceWire in a wide range of future onboard processing systems.

One of the principal aims of SpaceWire is the support of equipment compatibility and reuse at both the component and subsystem levels. In principle a datahandling system developed for an optical instrument, for example, can be used for a radar instrument by unplugging the optical sensor and plugging in the radar one. Processing units, massmemory units and downlink telemetry systems developed for one mission can be readily used on another mission, reducing the cost of development, improving reliability and most importantly increasing the amount of scientific work that can be achieved within a limited budget.

Integration and test of complex onboard systems is also supported by SpaceWire with ground support equipment plugging directly into the onboard datahandling system. Monitoring and testing can be carried out with a seamless interface into the onboard system.

SpaceWire is the result of the efforts of many individuals within the European Space Agency, European Space Industry and Academia.

Purpose

This Standard addresses the handling of payload data and control information on board a spacecraft. It is a standard for a high speed data link, which is intended to meet the needs of future, high capability, remote sensing instruments and other space missions. SpaceWire provides a unified high speed datahandling infrastructure for connecting together sensors, processing elements, massmemory units, downlink telemetry subsystems and EGSE equipment.

The purpose of this Standard is:

to facilitate the construction of highperformance onboard datahandling systems;

to help reduce system integration costs;

to promote compatibility between datahandling equipment and subsystems;

to encourage reuse of datahandling equipment across several different missions.

SpaceWire has taken into consideration two existing standards, IEEE 1355-1995 and ANSI/TIA/EIA-644. SpaceWire is specifically provided for use onboard a spacecraft.

Guide to this Standard

This Standard begins with clause 1 which introduces the scope of the Standard. Clause 2 then gives a list of applicable documents. Clause 3 provides the necessary definitions of terms and abbreviations and explains the notation used throughout the document. A brief overview of the Standard is given in clause 4 to familiarize the reader with the basic SpaceWire concepts, prior to the detailed specification of subsequent clauses.

The body of this Standard is presented in clauses 5 to 11, which ascend through the various normative levels of the Standard.

Clause 5 (Physical Level) covers cables, connectors, cable assemblies and printed circuit board tracks.

Clause 6 (Signal Level) deals principally with electrical characteristics, and coding and signal timing.

Clause 7 (Character Level) describes how data and control characters are encoded.

Clause 8 (Exchange Level) presents the way in which a SpaceWire link operates including link initialization, normal operation, error detection and error recovery.

Clause 9 (Packet Level) describes the way in which data is encapsulated in packets for transfer across a SpaceWire network.

Clause 10 (Network Level) deals with the structure and operation of a SpaceWire network.

The error recovery scheme is described as a whole in clause 11, which brings together the error detection, error recovery and error reporting mechanisms from all the protocol levels to aid comprehension.

This Standard concludes in clause 12 with a list of conformance statements, highlighting those parts of the Standard to conform to for SpaceWire compatibility of a system.

There are three annexes:

Annex A : The differences between this Standard and IEEE Standard 1355-1995 [1].

Annex B : State exit conditions for encoderdecoder state machine.

Annex C : Availability of referenced documents including web addresses for electronic versions.

Finally, a list of informative references is included in the Bibliography.

Scope

This Standard specifies the physical interconnection media and data communication protocols to enable the reliable sending of data at highspeed (between 2 Mb/s and 400 Mb/s) from one unit to another. SpaceWire links are fullduplex, pointtopoint, serial data communication links.

The scope of this Standard is the physical connectors and cables, electrical properties, and logical protocols that comprise the SpaceWire data link. SpaceWire provides a means of sending packets of information from a source node to a specified destination node. SpaceWire does not specify the contents of the packets of information.

This Standard covers the following protocol levels:

Physical level: Defines connectors, cables, cable assemblies and printed circuit board tracks.

Signal level: Defines signal encoding, voltage levels, noise margins, and data signalling rates.

Character level: Defines the data and control characters used to manage the flow of data across a link.

Exchange level: Defines the protocol for link initialization, flow control, link error detection and link error recovery.

Packet level: Defines how data for transmission over a SpaceWire link is split up into packets.

Network level: Defines the structure of a SpaceWire network and the way in which packets are transferred from a source node to a destination node across a network. It also defines how link errors and network level errors are handled.

This Standard may be tailored for the specific characteristics and constraints of a space project in conformance with ECSS-S-ST-00.

Normative references

The following normative documents contain provisions which, through reference in this text, constitute provisions of this ECSS Standard. For dated references, subsequent amendments to, or revision of any of these publications do not apply, However, parties to agreements based on this ECSS Standard are encouraged to investigate the possibility of applying the more recent editions of the normative documents indicated below. For undated references, the latest edition of the publication referred to applies.

|

ECSS-S-ST-00-01

|

ECSS system — Glossary of terms

|

|

ECSS-Q-ST-70-08

|

Space product assurance — Manual soldering of highreliability electrical connections

|

|

ECSS-Q-ST-70-26

|

Space product assurance — Crimping of highreliability electrical connections

|

|

ANSI/TIA/EIA-644

|

1995 Telecommunications Industry Association, “Electrical Characteristics of Low Voltage Differential Signaling (LVDS) Interface Circuits”, March 1996

|

|

ESCC 3401/071

|

Connectors, Electrical, Rectangular, Microminiature, Solder Buckert Contacts with EMI Backshell, based on type MDM

|

|

ESCC 3902/003

|

Cable, “Spacewire”, Round, Quad using Symmetric Cables, Flexible, –200 to +180 °C

|

Terms, definitions and abbreviated terms

Terms from other standards

For the purpose of this Standard, the terms and definitions from ECSSSST0001 apply.

Terms and definitions specific to the present standard

acknowledge

indication that a message has been received successfully by its intended destination

binder

layer of tape wrapped around one or more cables to keep them together in a fixed position

The tape is usually PTFE and is wrapped in an overlapping spiral along the length of the cables to bind.

bit error rate

ratio of the number of bits received in error to the total number of bits sent across a link

byte

eight bits

cargo

data to encapsulate in packets and transfer from a source to a destination

character

control character or data character

character level

protocol level that deals with the encoding of data and control characters into a bitstream

coding

translation from one set of bits to another new set of bits

content addressable memory

memory array which is accessed by searching for a match between an input data value in the contents of the memory array, where the output from the memory array is the index of the location that holds the searched for value

control character

character that is used to pass control information across a link

Control characters include the LChars (ESC and FCT) and the end of packet markers (EOP and EEP).

control code

sequence of two control characters: NULL (ESC + FCT) which is used to keep a link active, and TimeCode (ESC + data character) which is used to distribute system time information over a SpaceWire network

data character

data byte encoded ready for transfer across a link

data rate

rate at which the application data is transferred across a link

data signalling rate

rate at which the bits constituting control and data characters are transferred across a link

datastrobe

encoding scheme in which a sequence of data bits and clock is encoded as the original data bit sequence, together with another bit sequence (strobe) which changes state whenever the data bit sequence does not

decoding

act of translating an encoded set of bits to the original set of bits prior to coding

deserialization

transformation of a serial bit stream into a sequence of control or data characters

destination

node or unit that a packet is being sent to

destination address

route to be taken by a packet in moving from source to destination (path address) or an identifier specifying the destination (logical address)

destination list

list of destination identifiers which forms the destination address of a packet

destination identifier

address, or partial address, of the packet destination

driver

electronic circuit design to transmit signals across a particular transmission medium

end of packet marker

control character which indicates the end of a packet

error recovery scheme

method for handling errors detected within a SpaceWire link

exchange level

protocol level that defines the mechanisms for link initialization, link flow control, link error detection and link error recovery

filler

cylindrical piece of PTFE used to fill the gap between insulated wires or cables being grouped together and formed into a larger cable, which enhances the structure of the cable helping to keep the constituent wires in a fixed position relative to one another

flow control token (FCT)

control character used to manage the flow of data across a link, indicating that there is space for 8 more normalcharacters in the receiver buffer

host receive buffer

buffer within a host system for receiving data from a link interface

host system

system that a link interface is connected to

It can be, for example, a computer, sensor or memory unit and need not contain a computer or processor.

host transmit buffer

buffer within a host system for holding data prior to transmission through a link interface

input port

receive side of a link interface on a routing switch

jitter

random errors in the timing of a signal

laylength

number of twists per foot expressed as the length between one complete turn of a single end in the cable

link

bidirectional connection of one unit to another unit for passing data and control information

linkcharacter

control character used to manage the flow of data across a link

In this Standard, only ESC and FCT are used as link characters. NULL is formed from a pair of linkcharacters (ESC followed by FCT).

link destination

end of the link that is receiving a particular set of data or control information

link interface

SpaceWire interface comprising a transmitter which takes data from a host system and transmits it across a SpaceWire link, and a receiver which accepts data from a SpaceWire link and passes it to the host system

link receiver

receiver at one end of a link

link source

end of the link that is sending a particular set of data or control information

link transmitter

transmitter at one end of a link

logical address

data character at the start of a packet, which identifies the destination for the packet

low voltage differential signalling

particular form of differential signalling using low voltage swing signals

Mb/s

1 000 000 bits per second

network

set of units connected together via links and routing switches

network level

protocol level that defines the SpaceWire network routers and defines how packets of data are transferred across the network from source node to destination node

node

source or destination of a packet, which can be a processor, memory unit, sensor, EGSE or some other unit connected to a SpaceWire network

normalcharacter

data character or control character (EOP or EEP) that is passed from the exchange level to the packet level

NULL

token sent to keep the data link active when there are no data or control characters to send

output port

transmit side of a link interface on a routing switch

packet

sequence of normalcharacters comprising a destination address, packet cargo and an end of packet marker

packet level

protocol level that defines how data is organized in packets ready for transfer across a link or network

packet cargo

data to transfer from a source to a destination

path address

series of one or more data characters at the start of a packet which define the route to be taken across a SpaceWire network

physical level

protocol level that specifies the physical interconnection medium, e.g. cables and connectors

pseudoECL (PECL)

emittercoupled logic (ECL) referenced to +5 V

receiver

electronic circuit designed to receive signals sent across a particular transmission medium

router

routing switch

routing switch

switch connecting several links that routes packets from one link to another where the destination address of each packet by the switch is used to determine which link a packet is sent out on

serialization

transformation of a sequence of control or data characters into a serial bit stream

signal

measurable quantity that varies with time to transfer information by propagating along a transmission medium

signal level

protocol level which defines the electrical signals used for SpaceWire together with the datastrobe encoding and signal timing

skew

difference in time between the edges of two signals which should ideally be concurrent

source

node or unit sending a packet

TimeCode

code used to distribute system time over a SpaceWire network, which comprises ESC followed by a single data character holding six bits of the system time and two reserved bits

transmission medium

medium over which data is transferred e.g. screened twisted pair cables

transmitter

electronic circuit designed to transmit signals across a particular transmission medium

unit

box, board or subsystem, that can have one or more SpaceWire interfaces

Abbreviated terms

For the purpose of this Standard, the abbreviated terms from ECSSSST0001 and the following apply:

|

Abbreviation

|

Meaning

|

|

ACK

|

acknowledge

|

|

API

|

application programming interface

|

|

AWG

|

American wire gauge

|

|

BER

|

bit error rate

|

|

|

content addressable memory

|

|

DC

|

direct current

|

|

DMA

|

direct memory access

|

|

DS

|

datastrobe

|

|

DSDE

|

datastrobe, differentially ended

|

|

|

NOTE: Used in IEEE Standard 1355-1995 [1] to indicate a link with differentially encoded data and strobe signals.

|

|

DSP

|

digital signal processing

|

|

ECL

|

emittercoupled logic

|

|

EEP

|

error end of packet

|

|

|

NOTE: Used to indicate that an error occurred in the current packet.

|

|

EGSE

|

electronic ground support equipment

|

|

EMC

|

electromagnetic compatibility

|

|

EMI

|

electromagnetic interference

|

|

EOP

|

end of packet marker

|

|

ESA

|

European Space Agency

|

|

ESC

|

escape character

|

|

|

NOTE: Escape character is defined in the Character Level.

|

|

ESD

|

electrostatic discharge

|

|

FCT

|

flow control token

|

|

FIFO

|

first in first out memory

|

|

LChar

|

linkcharacter

|

|

LSB

|

least significant bit

|

|

LVDS

|

low voltage differential signalling

|

|

Mb/s

|

Megabits per second

|

|

MSB

|

most significant bit

|

|

NChar

|

normalcharacter

|

|

PCB

|

printed circuit board

|

|

PECL

|

pseudoECL

|

|

PFA

|

Perfluoral oxide Copolymer

|

|

|

NOTE: A type of plastic used to cover wires and cables.

|

|

PTFE

|

Polytetrafluroethylene

|

|

|

NOTE: A type of plastic used to cover wires and cables.

|

|

SCI

|

scaleable coherent interface

|

Conventions

Signal naming

All electrical signals are shown in uppercase letters.

The two signals making up a differential pair are given the suffixes + and – to indicate the positive and negative components of the differential signal, respectively.

The SpaceWire differential signals are referred to as D+,D- and S+,S- for Data and Strobe, respectively. When considering the driven end of a SpaceWire link these signals may be designated Dout+, Dout- and Sout+ and Sout- for Data and Strobe, respectively. Similarly the signals at the input end of a SpaceWire link are Din+, Din- and Sin+, Sin-.

Packet formats

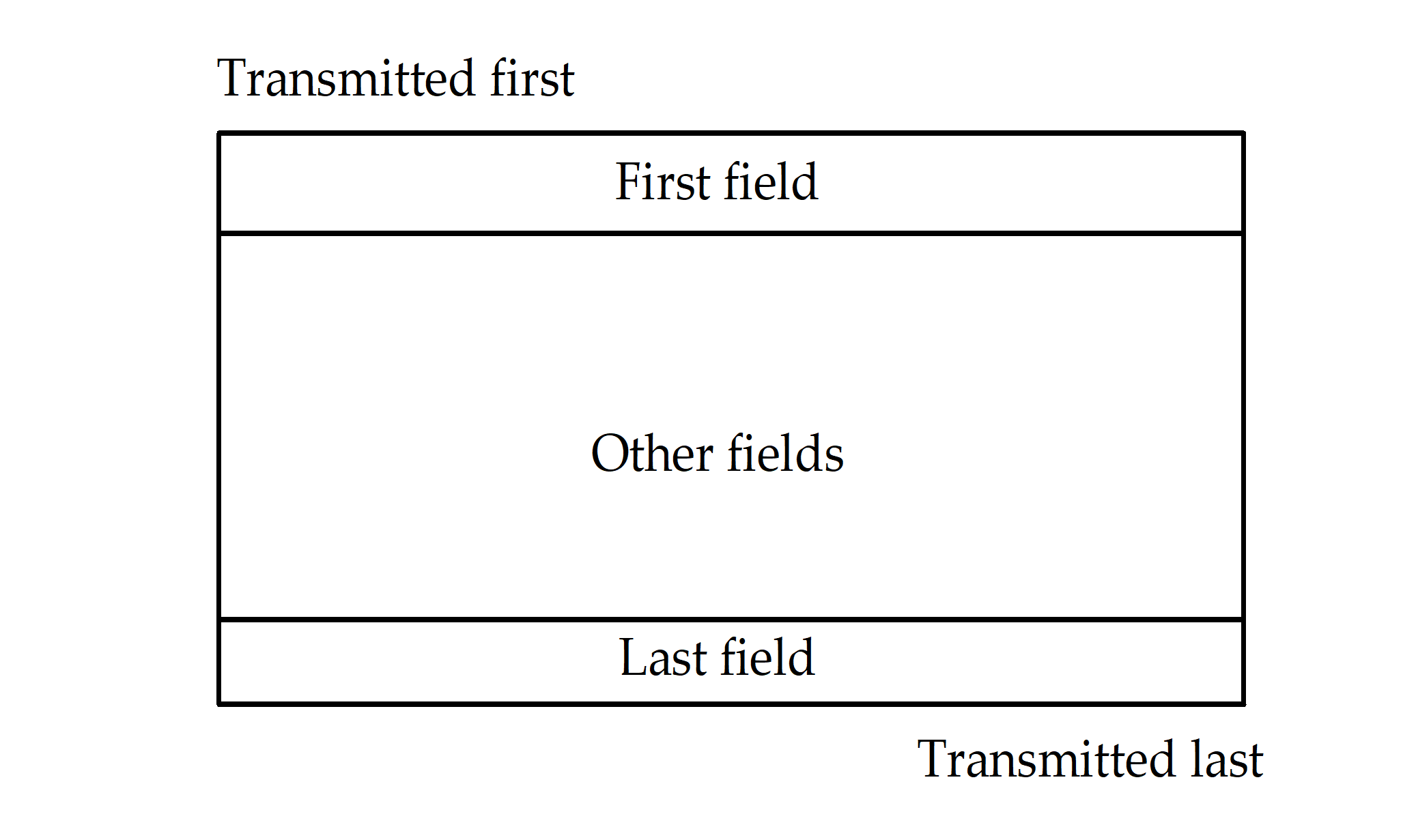

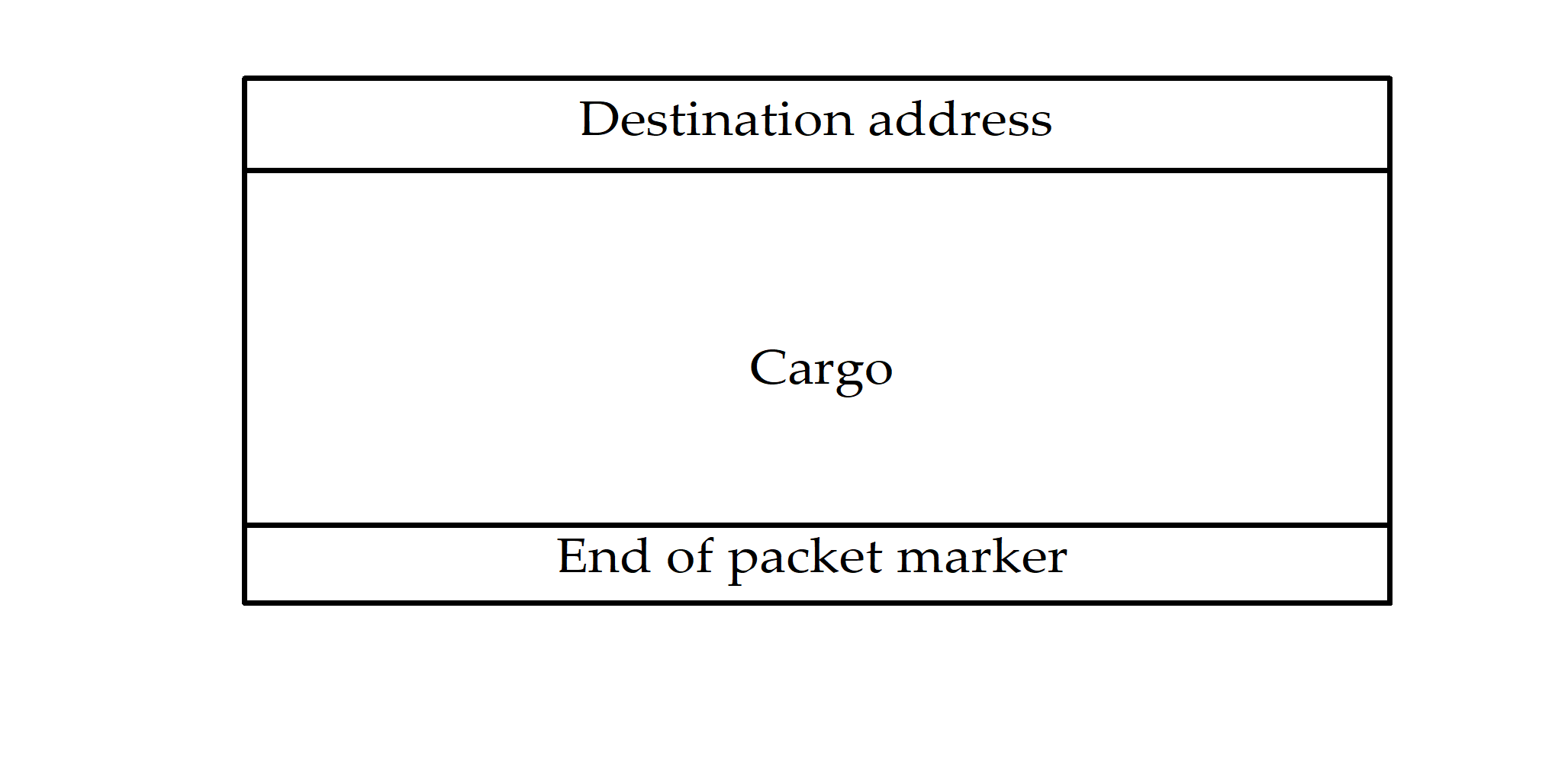

Packet formats are represented in two ways in this Standard. The first way is graphical and is shown in Figure 31. The field at the top is the one that is transmitted first.

Figure 31: Graphical packet notation

Figure 31: Graphical packet notation

The second packet representation is textual. Each field is enclosed in chevrons <>. The fields comprising a packet are written left to right in the order that they are transmitted. The example below is equivalent to that shown in Figure 31.

For example: <First field><Other fields><Last field>

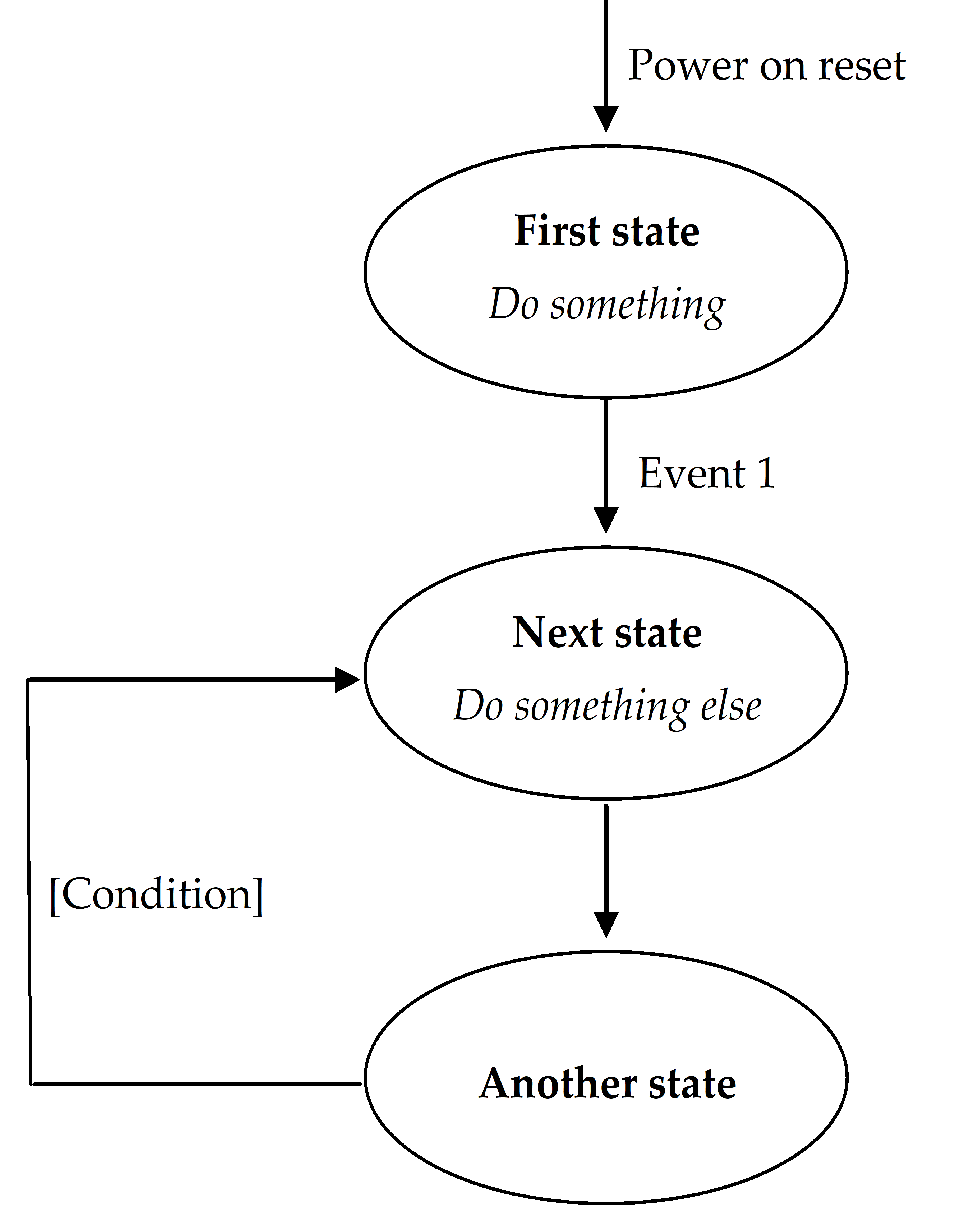

State diagram notation

All state diagrams in this Standard use the style shown in Figure 32. States are represented by ellipses with the state name written inside the ellipse in bold. Actions to take while in a particular state are written in italics inside the ellipse underneath the state name. Transitions from one state to another are indicated by arrows. The event that causes a transition is written alongside the arrow. Unconditional transitions are indicated by arrows without an event name written next to it. Reset conditions are indicated by transition arrows that start in empty space. Transitions can be enabled by a guarded condition so that the transition only takes place if the guard condition is true. Guard conditions are written in square brackets alongside the transition they affect.

State names referred to in the text of the Standard are in italics e.g. FirstState.

Figure 32: State diagram style

Figure 32: State diagram style

Overall description

Overview

This clause provides an overview of the Standard giving the rationale behind key decisions made in the development of the Standard.

SpaceWire takes into consideration the “DS-DE” part of IEEE Standard 1355-1995 [1], as well as ANSI/TIA/EIA-644 and IEEE Standard 1596.3-1996 [2] Low Voltage Differential Signalling (LVDS). See annex A for details of the main differences between SpaceWire and IEEE Standard 1355-1995 and the reasons for those differences.

SpaceWire is a fullduplex, bidirectional, serial, pointtopoint data link. It encodes data using two differential signal pairs in each direction. That is a total of eight signal wires, four in each direction.

Physical level

Overview

The physical level of the Standard covers cables, connectors, cable assemblies and printed circuit board (PCB) tracks. SpaceWire was developed to meet the EMC specifications of typical spacecraft.

Cables

The SpaceWire cable comprises four twisted pair wires with a separate shield around each twisted pair and an overall shield.

To achieve a high data signalling rate with SpaceWire over distances up to 10 m a cable with the following characteristics is used:

characteristic impedance matched to the line termination impedance;

low signalsignal skew between each signal in a differential pair and between Data and Strobe pairs;

low signal attenuation;

low crosstalk;

good EMC performance.

Connectors

The SpaceWire connector has eight signal contacts plus a screen termination contact. A ninepin microminiature Dtype is specified as the SpaceWire connector. This type of connector is available qualified for space use.

Cable assemblies

SpaceWire cable assemblies are made from SpaceWire cable up to 10 m in length terminated at each end by ninepin microminiature Dtype plugs.

Printed circuit board tracks

SpaceWire includes specifications for running SpaceWire signals over printed circuit boards including backplanes using pairs of tracks with 100 differential impedance.

Electromagnetic compatibility

SpaceWire was developed to meet the electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) specifications of typical spacecraft. EMC testing was performed by Patria Finavitec Oy with support from the following EMC specifications derived from the EMC specifications for the Rosetta [3] and other ESA missions. The testing covered:

Radiated emission, electric and magnetic fields;

Radiated susceptibility, electric and magnetic fields;

Conducted susceptibility;

Conducted emission;

Electrostatic discharge;

Signalling rate;

Bit error rate;

Fault isolation; and

Power consumption.

The EMC test results are provided in [4].

Signal level

Overview

The signal level part of this Standard covers signal voltage levels, noise margins and signal encoding.

Signal level and noise margins

Low voltage differential signalling or LVDS (ANSI/TIA/EIA644) is specified as the signalling technique to use in SpaceWire.

LVDS uses balanced signals to provide very highspeed interconnection using a low voltage swing (350 mV typical). The balanced or differential signalling provides adequate noise margin to enable the use of low voltages in practical systems. Low voltage swing means low power consumption at high speed. LVDS is appropriate for connections between boards in a unit, and unit to unit interconnections over distances of 10 m or more.

The signalling levels used by LVDS are illustrated in Figure 41.

Figure 41: LVDS signalling levels

A typical LVDS driver and receiver are shown in Figure 42, connected by a media (cable or PCB traces) with 100 differential impedance.

Figure 42: LVDS operation

The LVDS driver uses current mode logic. A constant current source of around 3,5 mA provides the current that flows out of the driver, along the transmission medium, through the 100 termination resistance and back to the driver via the transmission medium. Two pairs of transistor switches in the driver control the direction of the current flow through the termination resistor. When the driver transistors marked “+” in Figure 42 are turned on and those marked “-” are turned off, current flows as indicated by the arrows on the diagram creating a positive voltage across the termination resistor. When the two driver transistors, marked “-”, are turned on and those marked “+” are turned off, current flows in the opposite direction producing a negative voltage across the termination resistor. LVDS receivers are specified to have high input impedance so that most of the current flows through the termination resistor to generate around 350 mV with the nominal 3,5 mA current source.

LVDS has several features that make it very attractive for data signalling [5]:

Near constant total drive current (+3,5 mA for logic 1 and -3,5 mA for logic 0) which decreases switching noise on power supplies.

High immunity to ground potential difference between driver and receiver - LVDS can tolerate at least 1 V ground difference.

High immunity to induced noise because of differential signalling normally using twistedpair cable.

Low EMI because small equal and opposite currents create small electromagnetic fields which tend to cancel one another out.

Not dependent upon particular device supply voltages.

Simple 100 termination at receiver.

Failsafe operation, i.e. the receiver output goes to the high state (inactive) whenever

the receiver is powered and the driver is not powered;

the inputs are short circuited;

input wires are disconnected.

Power consumption is typically 50 mW per driver - receiver pair for LVDS compared to 120 mW for ECL or PECL.

The following two standards deal with LVDS

ANSI/TIA/EIA-644 that defines the driver output characteristics and the receiver input characteristics only.

IEEE Standard 1596.3 that defines the signalling levels used and the encoding for packet switching used in SCI data transfers [2].

The signal levels and noise margins for SpaceWire are defined taking into consideration the ANSI/TIA/EIA-644 since this deals with LVDS only whereas IEEE Standard 1596.3 [2] is concerned with the use of LVDS specifically for SCI.

Data encoding

SpaceWire uses DataStrobe (DS) encoding. This is a coding scheme which encodes the transmission clock with the data into Data and Strobe so that the clock can be recovered by simply XORing the Data and Strobe lines together. The data values are transmitted directly and the strobe signal changes state whenever the data remains constant from one data bit interval to the next. This coding scheme is illustrated in Figure 43. The DS encoding scheme is also used in the IEEE Standard 1355-1995 [1] and IEEE 1394-1995 (Firewire) Standard [6].

The reason for using DS encoding is to improve the skew tolerance to almost 1bit time, compared to 0,5 bit time for simple data and clock encoding.

Figure 43: DataStrobe (DS) encoding

A SpaceWire link comprises two pairs of differential signals, one pair transmitting the D and S signals in one direction and the other pair transmitting D and S in the opposite direction. That is a total of eight wires for each bidirectional link.

Character level

SpaceWire takes into consideration the character level protocol defined in IEEE Standard 1355-1995 [1], but it additionally includes TimeCodes to support the distribution of system time.

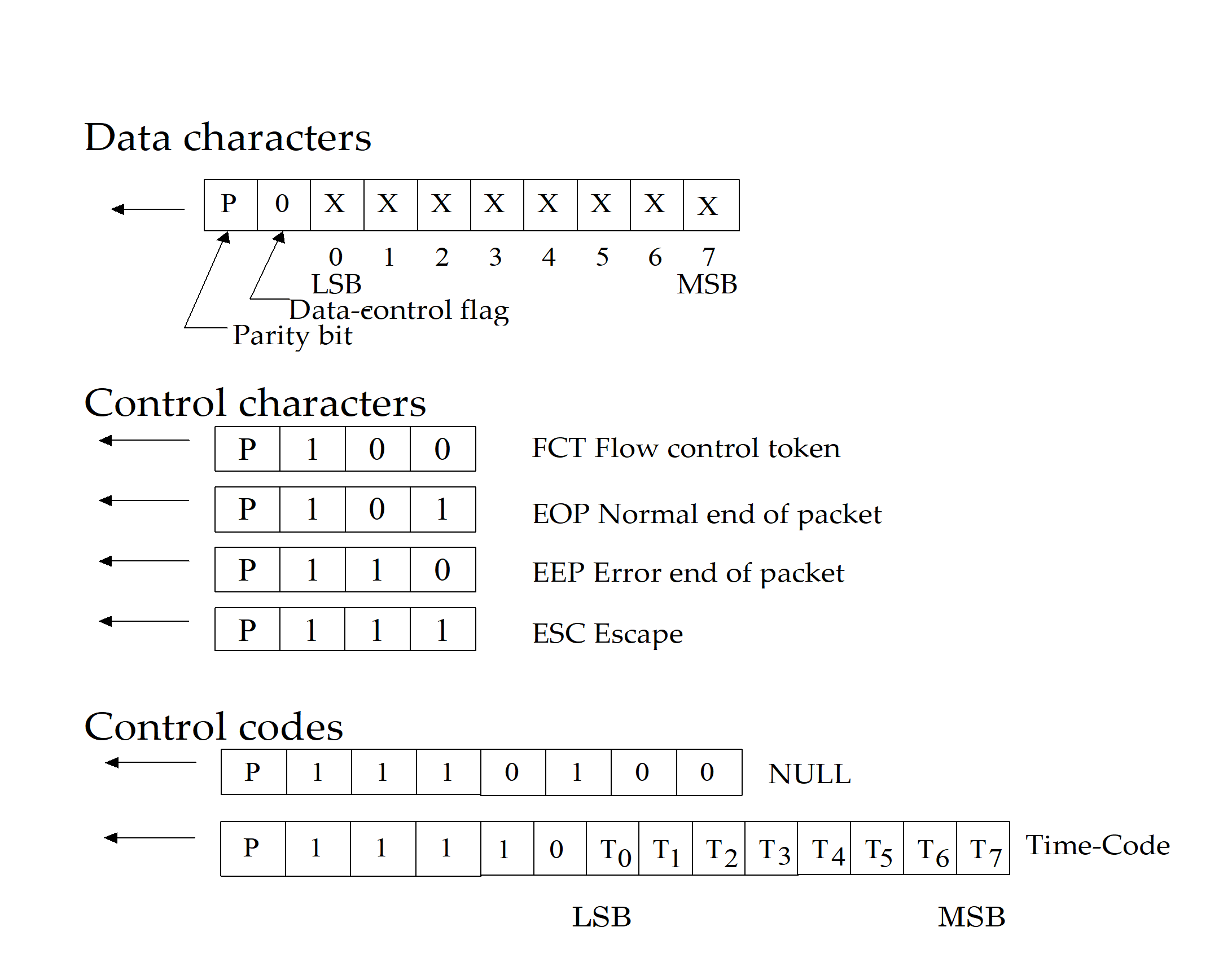

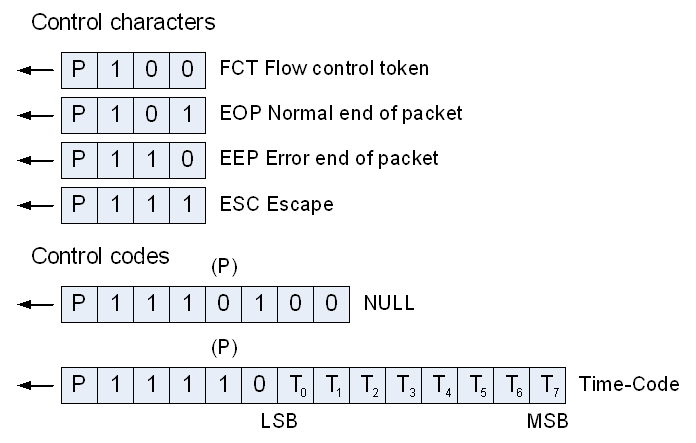

There are two types of characters:

Data characters which hold an eightbit data value, transmitted least significant bit first. Each data character contains a parity bit, a datacontrol flag and the eight bits of data. The parity bit covers the previous eight bits of a data character or two bits of a control character, the current parity bit and the current datacontrol flag. It is set to produce odd parity so that the total number of 1’s in the field covered is an odd number. The datacontrol flag is set to zero to indicate that the current character is a data character.

Control characters which hold two control bits. Each control character is formed from a parity bit, a datacontrol flag and two control bits. The datacontrol flag is set to one to indicate that the current character is a control character. Parity coverage is similar to that for a data character. One of the four possible control characters is the escape code (ESC). This can be used to form control codes. Two control codes are specified and valid which are the NULL code and the TimeCode.

NULL is formed from ESC followed by the flow control token (FCT). NULL is transmitted whenever a link is not sending data or control tokens, to keep the link active and to support link disconnect detection.

The TimeCode is used to support the distribution of system time across a network. A TimeCode is formed by ESC followed by a single datacharacter.

The data and control characters are illustrated in Figure 44.

Figure 44: Data and control characters

Figure 44: Data and control characters

Exchange level

The exchange level protocol is a significantly more capable version than that defined in IEEE Standard 1355-1995 [1] and provides the following services:

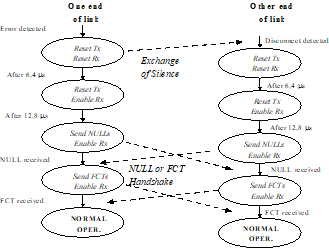

Initialization: Following reset the link output is held in the reset state until it is instructed to start and attempts to make a connection with the link interface at the other end of the link. A connection is made following a handshake that ensures both ends of the link are able to send and receive characters successfully. Each end of the link sends NULLs, waits to receive a NULL, then sends FCTs and waits to receive an FCT. Since a link interface cannot send FCTs until it has received a NULL, receipt of one or more NULLs followed by receipt of an FCT means that the other end of the link has received NULLs successfully and that full connection is achieved.

Flow control: A transmitter can only transmit NChars (normal characters, which are data characters, EOP or EEP) if there is space for them in the host system receive buffer at the other end of the link. The host system indicates that there is space for eight more NChars by requesting the link transmitter to send a flow control token (FCT). The FCT is received at the other end of the link (end B) enabling the transmitter at end B to send up to eight more NChars. If there is more room in the host receive buffer then multiple FCTs can be sent, one for every eight spaces in the receive buffer. Correspondingly, if multiple FCTs are received then it means that there is a corresponding amount of space available in the receiver buffer, e.g. four FCTs means that there is room for 32 NChars.

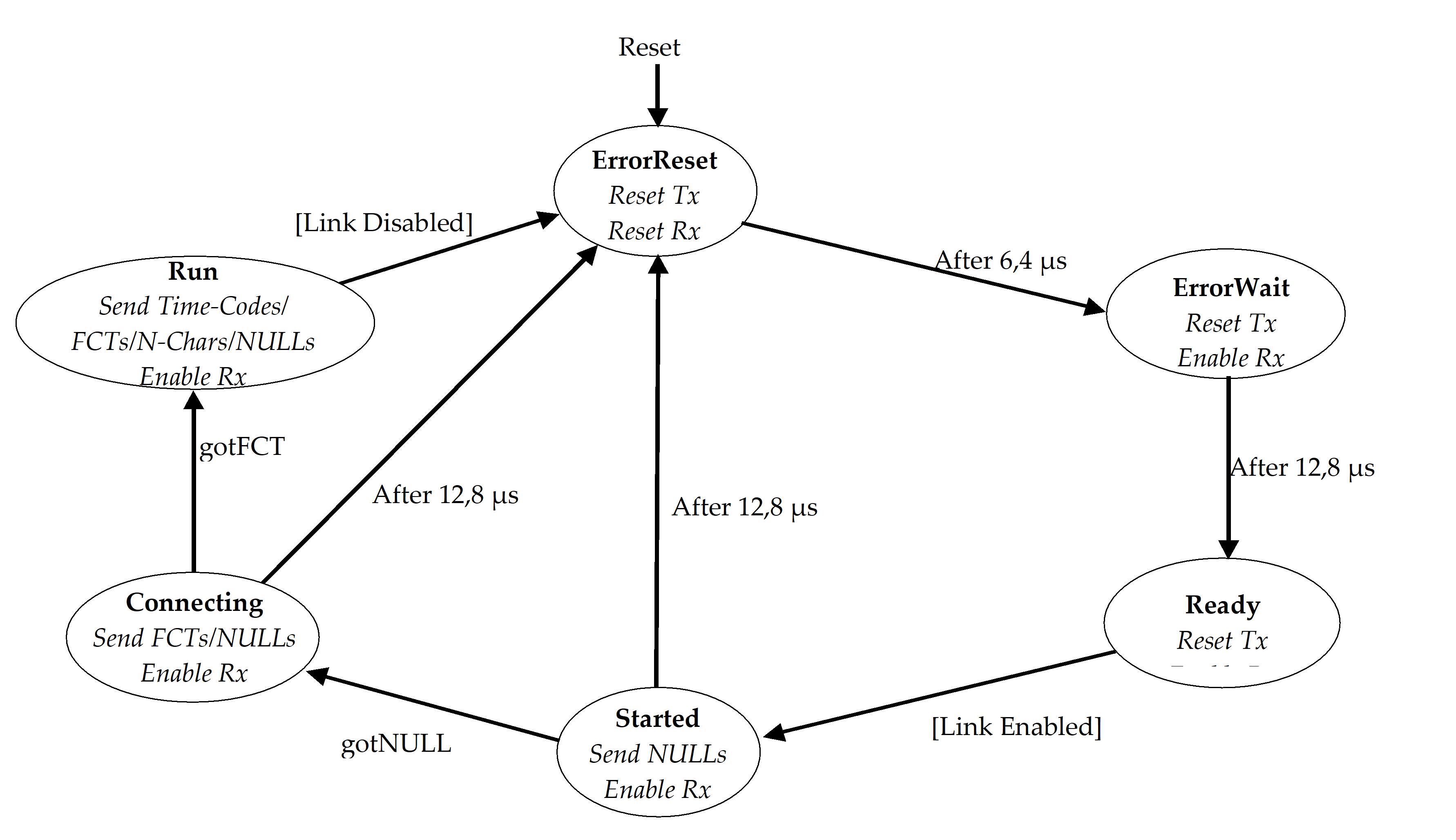

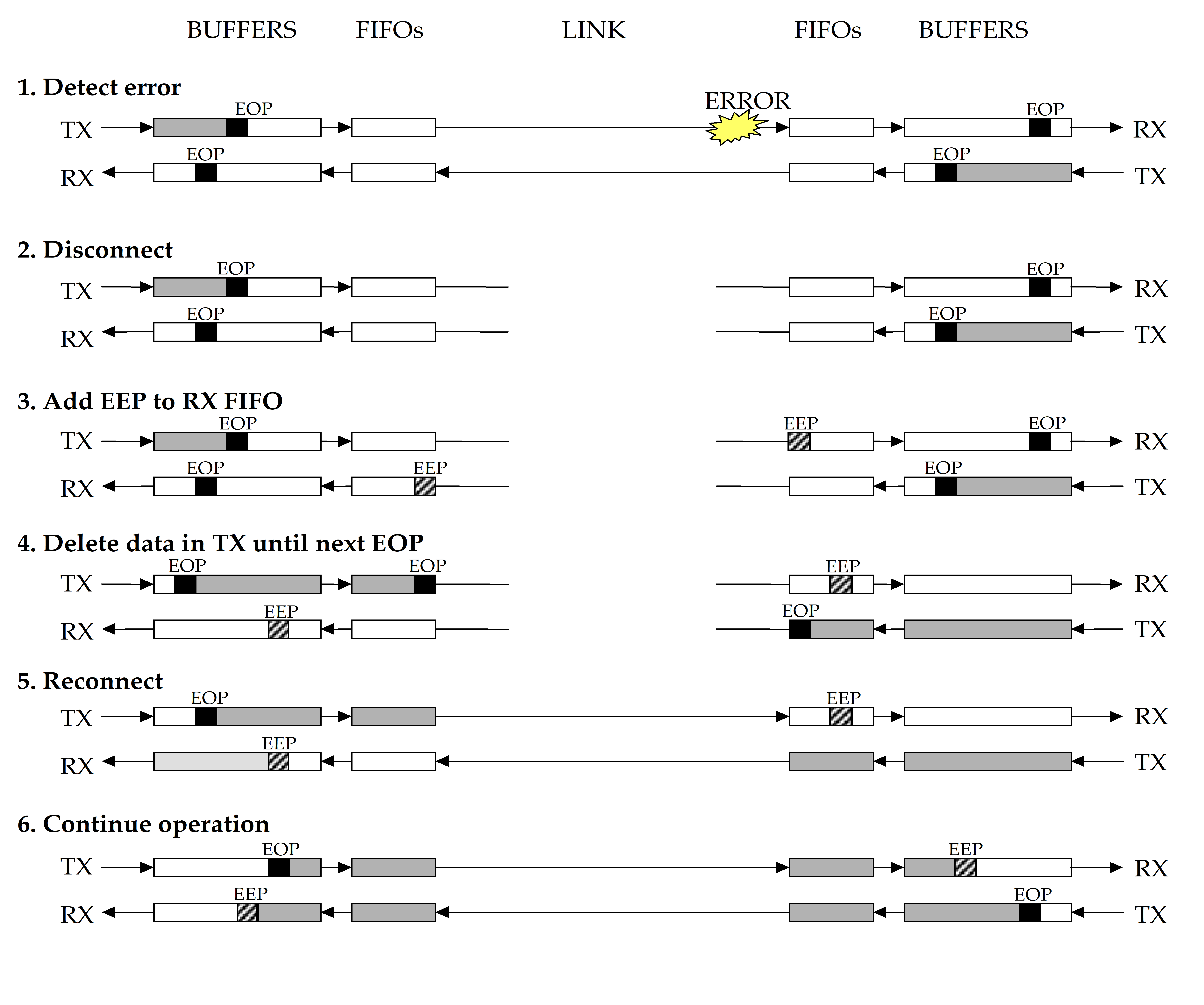

Detection of disconnect errors: Link disconnection is detected when following reception of a data bit no new data bit is received within a link disconnect timeout window (850 ns). Once a disconnection error is detected, the link attempts to recover from the error (see Figure 45).

Detection of parity errors: Parity errors occurring within a data or control character are detected when the next character is sent, since the parity bit for a data or control character is contained in the next character. Once a parity error is detected, the link attempts to recover from the error (see Figure 45).

Link error recovery: Following an error or reset the link attempts to resynchronize and restart using an “exchange of silence” protocol (see Figure 45). The end of the link that is either reset or that finds an error, ceases transmission. This is detected at the other end of the link as a link disconnect and that end stops transmitting too. The first link resets its input and output for 6,4 s to ensure that the other end detects the disconnect. The other end also waits for 6,4 s after ceasing transmission. Each link then waits a further 12,8 s before starting to transmit. These periods of time are sufficient to ensure that the receivers at both ends of the link are ready to receive characters before either end starts transmission. The two ends of the link go through the NULL or FCT handshake to reestablish a connection and ensure proper character synchronization.

Figure 45: Link restart

Figure 45: Link restart

Packet level

The packet level protocol follows the packet level protocol defined in IEEE Standard 1355-1995 [1]. It defines how data is encapsulated in packets for transfer from source to destination. The format of a packet is illustrated in Figure 46.

Figure 46: Packet format

Figure 46: Packet format

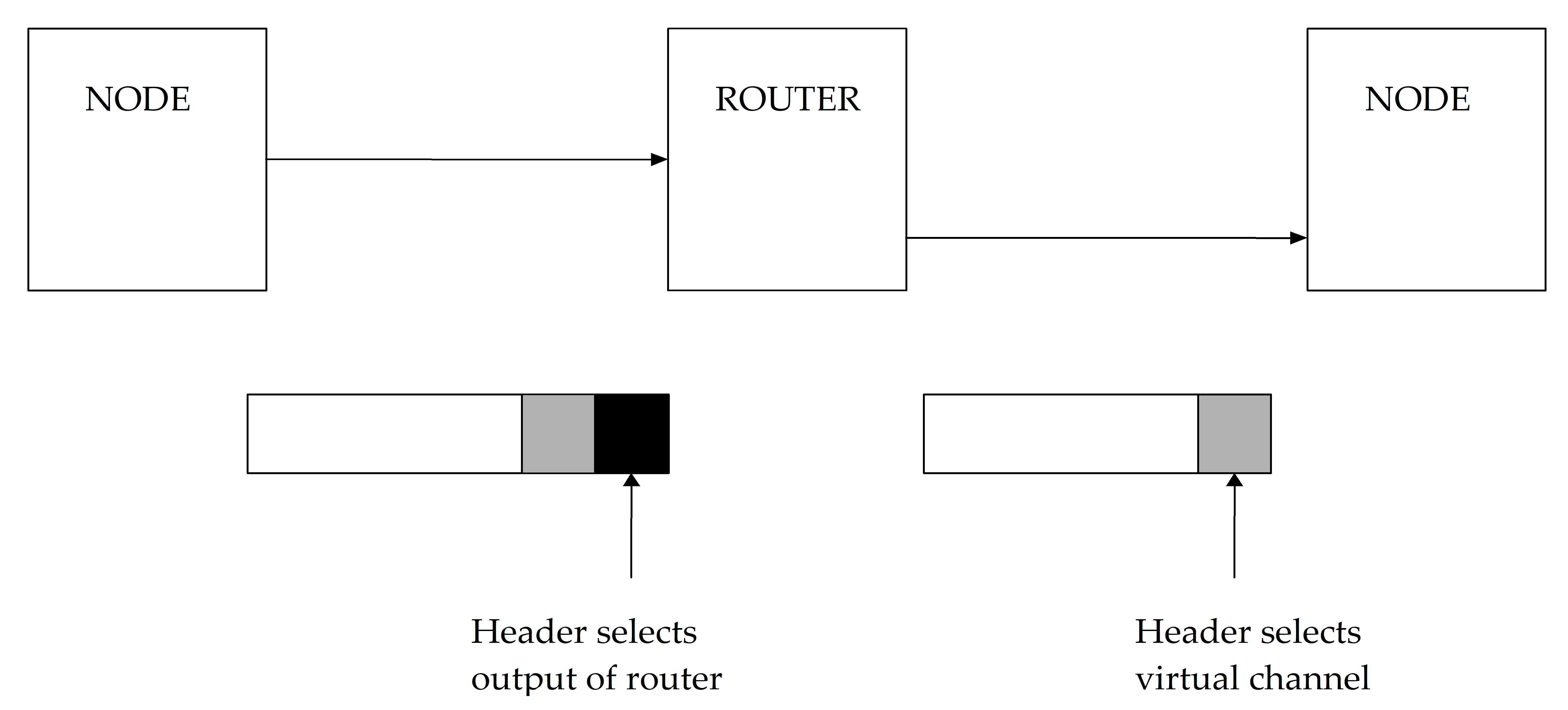

The “destination address” is a list of zero or more data characters that represent the destination identity. This list of data characters represents either the identity code of the destination node or the path that the packet takes to get to the destination node.

The “cargo” is the data to transfer from source to destination.

The “end of packet marker” is used to indicate the end of a packet. Two end of packet markers are defined:

EOP normal end_of_packet marker - indicates end of packet;

EEP error end_of_packet marker - indicates that the packet is terminated prematurely due to a link error.

Since there is no start_of_packet marker, the first data character following an end_of_packet marker (either EOP or EEP) is regarded as the start of the next packet.

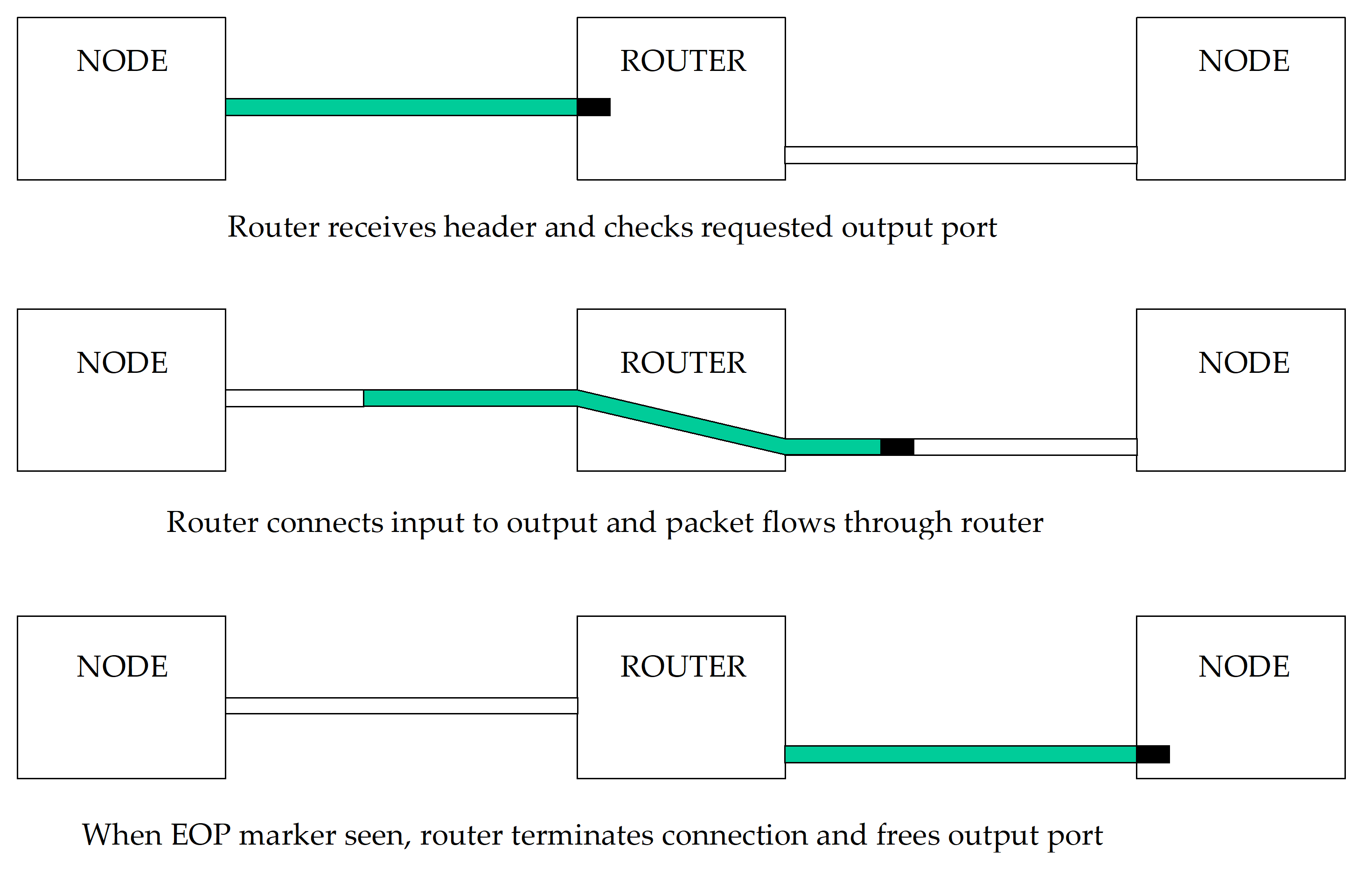

The packet level protocol provides support for packet routing via wormhole routing switches [7].

Network level

The network level defines what a SpaceWire network is, describes the components that make up, explains how packets are transferred across it, and details the manner in which it recovers from errors.

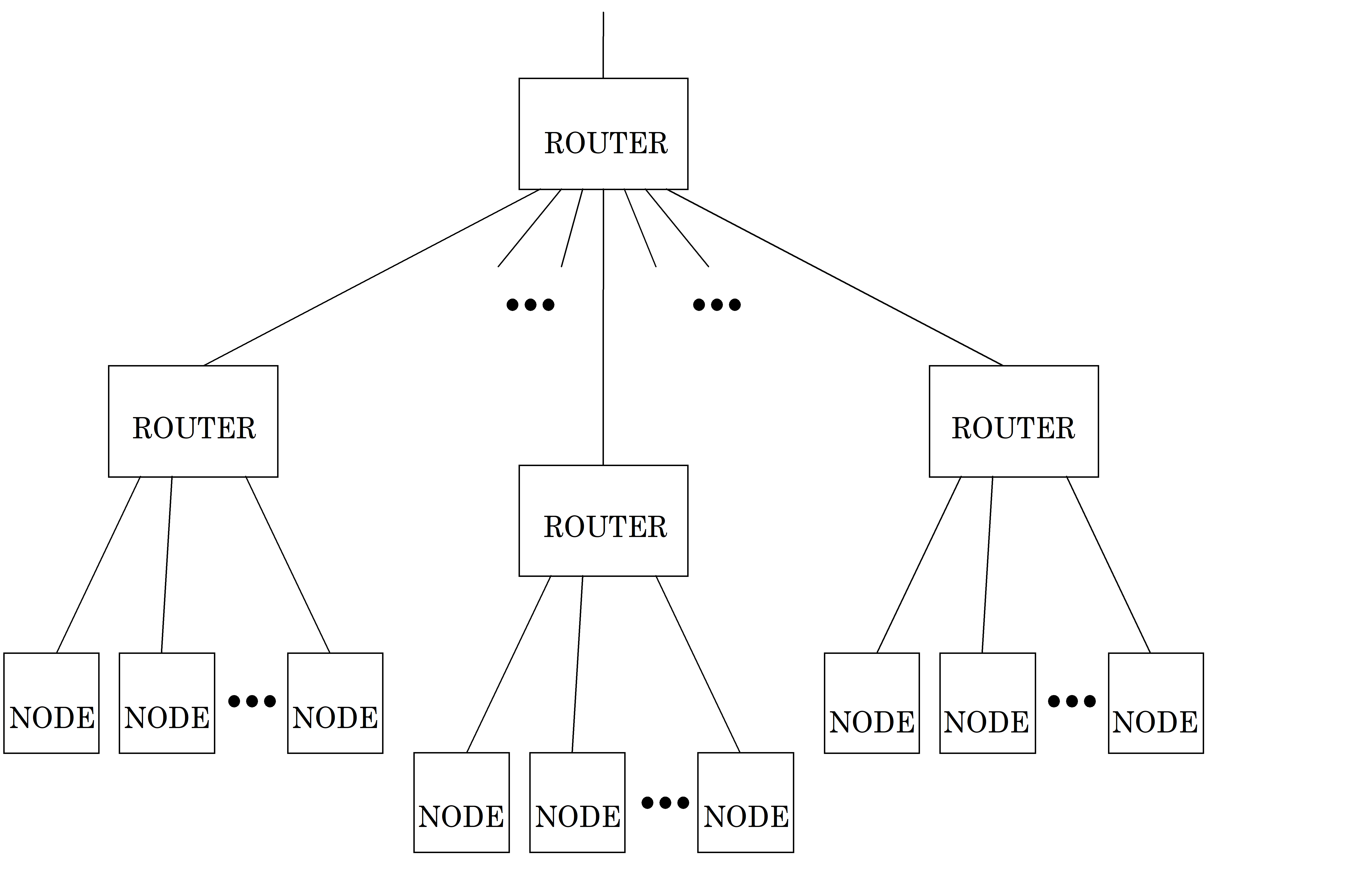

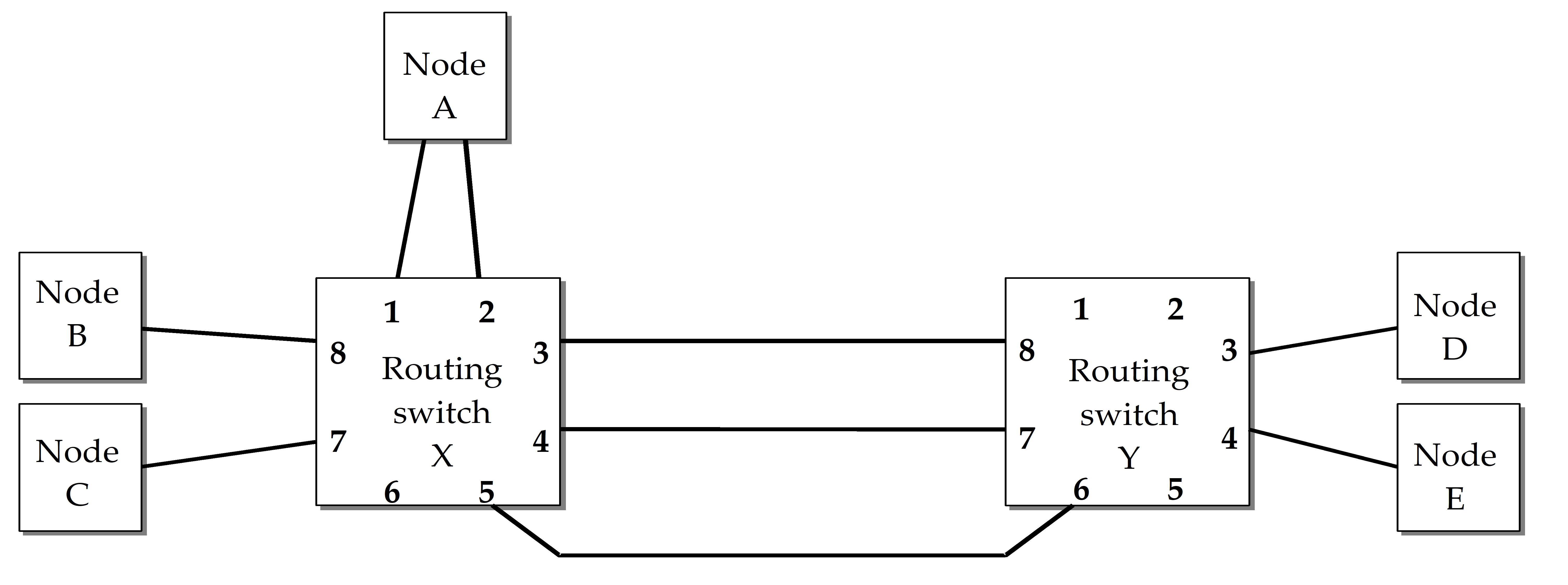

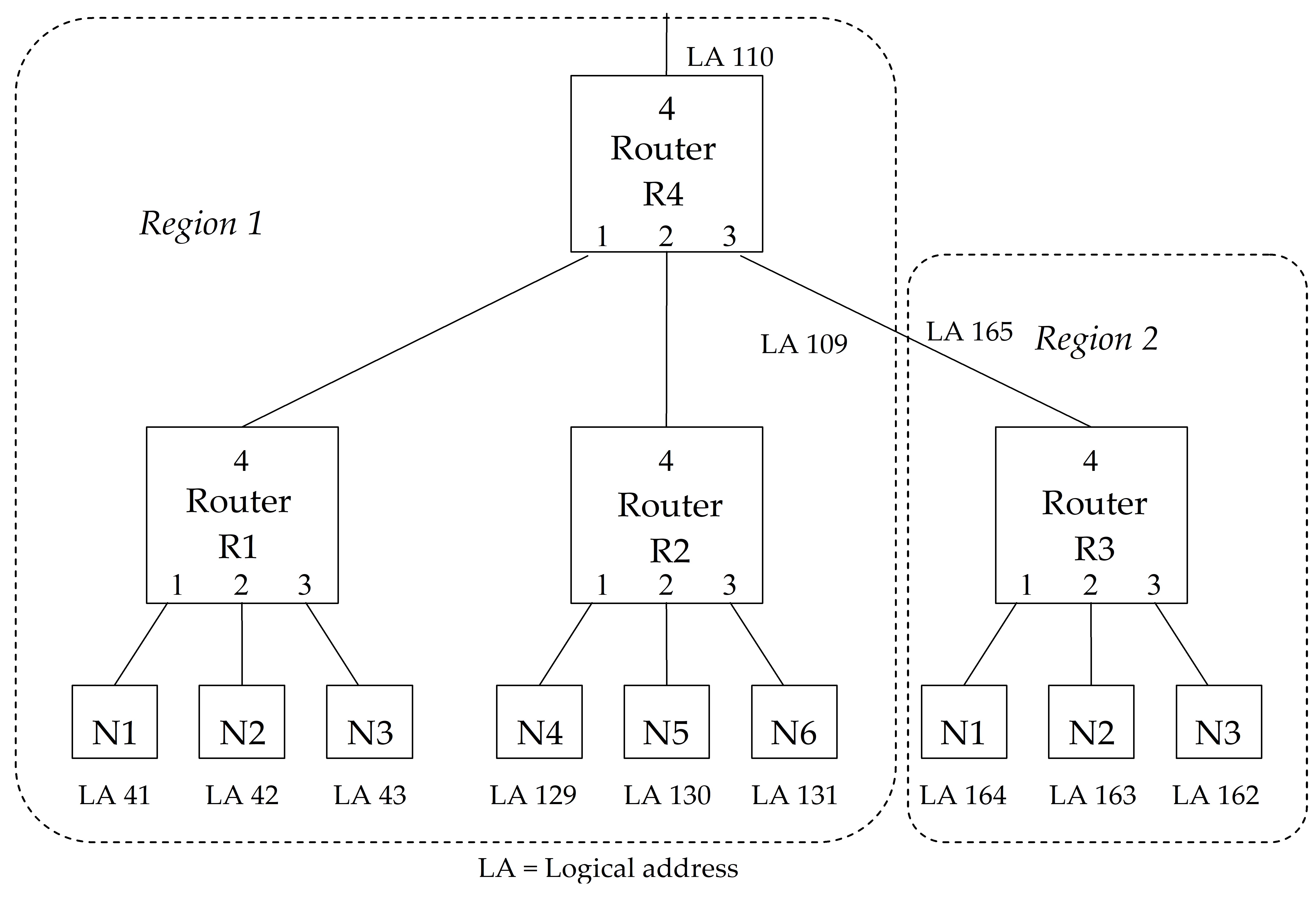

A SpaceWire network is made up of a number of SpaceWire nodes interconnected by SpaceWire routing switches. SpaceWire nodes are the sources and destinations of packets and provide the interface to the application systems. SpaceWire nodes can be directly connected together using SpaceWire links or they can be interconnected via SpaceWire routing switches using SpaceWire links to make the connection between node and routing switch. A SpaceWire routing switch has several link interfaces connected together by a switch matrix, which allows any link input to pass the packets that it receives on to any link output for retransmission.

Application programming interface

The application programming interface (API) is not defined in this Standard. However, a typical application interface comprises the following services:

Open link: Starts a link interface and attempts to establish a connection with the link interface at the other end of the link.

Close link: Stops a link and breaks the connection.

Write packet: Sends a packet out of the link interface.

Read packet: Reads a packet from the link interface.

Status and configuration: Reads the current status of the link interface and sets the link configuration.

Physical level (normative)

Overview

The physical level provides the actual interface between nodes including both the mechanical and electrical interface. This clause covers:

cable construction,

connectors,

cable assemblies, and

PCB and backplane tracking.

Cables

Generic

The SpaceWire cable shall be constructed according to ESCC 3902/003 and the specific details given in the following clauses.

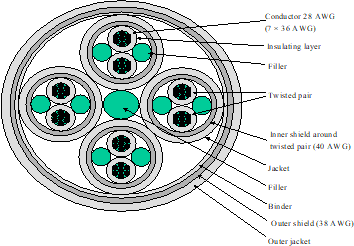

The SpaceWire cable shall comprise four twisted pair wires with a separate shield around each twisted pair and an overall shield as illustrated in Figure 51.

Figure 51: SpaceWire cable construction

Figure 51: SpaceWire cable construction

Inner conductors

Conductor

Each signal wire shall be 28 AWG, constructed from seven strands of 36 AWG silvercoated, highstrength copper alloy.

The thickness of the silver coating shall be 2,0 m minimum.

Tensile characteristics

The minimum elongation of each strand shall be 6,0 %.

The tensile strength of each strand shall be at least 350 N/mm2.

Insulator

Each signal shall be insulated using expanded, microporous PTFE with only those additives for processing and pigmentation.

Insulator colour

The insulator around the signal wires shall be white.

Electrical characteristics

The maximum DC resistance of the inner conductor shall be 256 /km.

Twisted pair

Laylength

The laylength of the two insulated conductors comprising a differential signal pair shall not be less than 12 times and not more than 16 times the outside diameter of the unshielded twisted pair.

Fillers

Fillers shall be used with the differential signal pairs so as to ensure a smooth and uniform diameter under the shielding in order to contribute to a uniform impedance over the cable.

Filler material

The filler material as used for the differential signal pairs shall be expanded microporous PTFE with only those additives for processing.

Construction of filler

The filler material shall be extruded or wrapped from tapes to a diameter of 1,0 mm.

Shield

Each differential signal pair shall be shielded by a braided shield.

The braided shield type shall be of pushback type and provide not less than 90 % coverage.

Shield wire size

The shield wire size shall be 40 AWG.

Shield material

All strands used in the manufacture of the braided shield shall be silvercoated, soft or annealed oxygenfree high conductivity copper.

The thickness of silver shall be 2,5 m minimum.

Any strand shall show an elongation of 10 % minimum.

Protective sheath

The protective sheath for the shielded differential signal pairs shall be a layer of extruded fluorpolymer PFA with only those additives for processing and pigmentation.

Protective sheath wall thickness

The wall thickness of the protective sheath for the shielded differential signal pair shall be 0,15 mm nominal.

Protective sheath colour

The jacket colour of the differential signal pairs shall be white.

Characteristic impedance

The characteristic impedance of each differential signal pair shall be (100 6) differential impedance.

Skew

The skew between each signal in each differential signal pair shall be less than 0,1 ns/m.

Complete cable

Construction

Four sets of differential signal pairs shall be twisted together not less than 12 times and not more than 16 times the outside diameter of two shielded and jacketed differential signal pairs.

Filler

A filler shall be used in the centre of the four differential signal pairs so as to ensure a smooth and uniform diameter under the shielding in order to contribute to a uniform impedance over the cable.

Filler material

The filler material as used for the complete cable shall be microporous PTFE with only those additives for processing.

Construction of filler

The filler material shall be extruded or wrapped from tapes to a diameter of 1,0 mm.

Binder

A binder shall be applied over the four differential signal pairs and central filler to keep the signal pairs and filler together in a fixed position.

Binder material

The material shall be virgin, wrapped, expanded microporous PTFE with only those additives for processing.

Binder construction

The material shall be wrapped with an overlap of 50 % maximum.

Outer shield

The set of four jacketed and screened differential signal pairs shall be shielded by an outer braided shield.

The braided shield type shall be of pushback type and provide not less than 90 % coverage.

Outer shield wire size

The shield wire size shall be 38 AWG.

Outer shield material

All strands used in the manufacture of the braided shield shall be silvercoated, soft or annealed oxygenfree high conductivity copper.

The thickness of silver shall be 2,5 m minimum.

Any strand shall show an elongation of 10 % minimum.

Shield isolation

The twisted pair shields shall not make contact with one another nor with the outer shield.

Outer jacket

The outermost jacket over the four twisted screened and jacketed differential signal pairs shall be a layer of extruded Fluoropolymer PFA with only those additives for processing and pigmentation.

Outer jacket wall thickness

The wall thickness of the jacket for the shielded differential signal pair shall be 0,25 mm nominal.

Jacket colour

The colour of the jacket shall be white.

There shall be no identifying marking on the cable jacket.

Applying pressure to the cable during the marking process can adversely affect the electrical properties of the cable.

Signal skew

The skew between the parts of the differential signal in one differential signal pair shall be 0,1 ns/m maximum.

The skew between one differential signal pair and each other differential signal pair within the cable shall be 0,15 ns/m maximum.

Cable physical parameters

Cable diameter

The outside diameter of the complete cable shall be 7 mm maximum.

Cable minimum bend radius

The minimum bend radius of complete cable shall be 45 mm.

Adhesion of inner conductor

The minimum stripping force shall be 1,0 N.

Cable weight

The maximum weight of the SpaceWire cable shall be 80 g/m.

Cable maximum ratings

The maximum ratings defined in Table 1 shall be met.

The total temperature of the wire (i.e. ambient plus rise) shall not exceed the maximum operating temperature of the wire.

Table 51: SpaceWire cable maximum ratings

|

No.

|

Characteristics

|

Symbol

|

Maximum ratings

|

Unit

|

Remarks

|

|

1

|

Operating voltage (continuous)

|

Vop

|

200

|

Vrms

|

|

|

2

|

Current

|

I

|

1,5

|

A

|

|

|

3

|

Operating rate

|

FM

|

400

|

Mb/s

|

|

|

4

|

Operating temperature range

|

Top

|

-200 to +180

|

°C

|

Tamb a

|

|

5

|

Storage temperature range

|

Tstg

|

-200 to +180

|

°C

|

|

|

a The specified current generates a temperature rise of approximately 50 C above ambient temperature in a vacuum environment. See 5.2.5.5b for precautions to take on the total temperature of the wire.

| |||||

Connectors

General

The SpaceWire connector shall be a nine contact microminiature Dtype with solder contacts, as defined in ESCC 3401/071, or crimp contacts.

Receptacles

Receptacles shall be used on board and unit assemblies.

Receptacles shall be equipped with female contacts.

Receptacles with flying leads should be used for connection to a PCB rather than PCB mounting connectors to improve mechanical shock and vibration resistance of the unit.

Soldering shall conform to ECSS-Q-ST-70-08.

Crimping shall conform to ECSS-Q-ST-70-26.

Plugs

Plugs shall be used on cable assemblies.

Plugs shall be equipped with male contacts as follows:

- The SpaceWire conductors directly soldered or crimped to the contacts as described in clause 5.4.

- The overall shield of the SpaceWire connected to the shell via an EMI backshell.

Soldering shall conform to ECSS-Q-ST-70-08.

Crimping shall conform to ECSS-Q-ST-70-26.

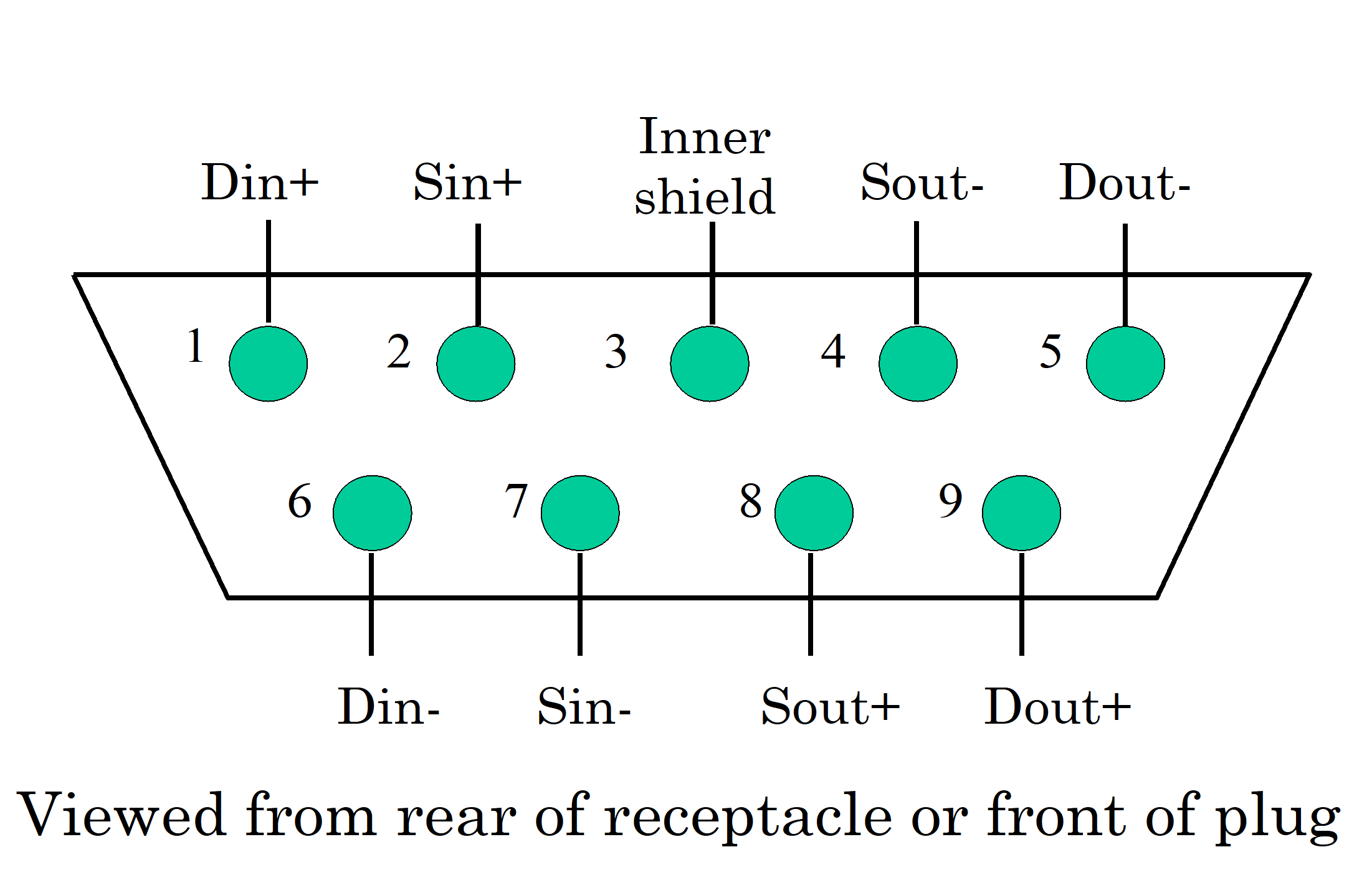

Connector contact identification

The connector contact identification given in Table 52 and Figure 52 shall be used.

Table 52: Connector contact identification

|

Contact number

|

Signal name

|

|

1

|

Din+

|

|

2

|

Sin+

|

|

3

|

Inner shield

|

|

4

|

Sout-

|

|

5

|

Dout-

|

|

6

|

Din-

|

|

7

|

Sin-

|

|

8

|

Sout+

|

|

9

|

Dout+

|

Figure 52: SpaceWire connector contact identification

Figure 52: SpaceWire connector contact identification

Inner shield connection

The inner shield connection shall be connected to the inner shield of the SpaceWire cable.

This inner shield of the SpaceWire cable should be connected to signal ground according to the EMC requirements of the mission.

The connection referred in b. should be performed via a parallel resistor and capacitor.

See clause 5.4 for the cable connection to pin 3 of the connector.

Flying lead connectors

Flying lead connectors should be used for connection to a PCB.

Flying lead connectors used for connection to a PCB should have all the leads cropped to the same short length (less than 25 mm) and the wires comprising the differential signal pairs should be twisted together.

This helps to minimize the discontinuity in impedance caused by the connector.

PCB mounting connectors

PCB mounting rightangled connectors should not be used.

If a PCB mounting rightangled connector is used, signal path length compensation shall be performed by adjusting the length of tracks on the PCB, as follows.

If a PCB mounting rightangled connector is used, signals connected to the top row shall be given correspondingly shorter PCB track lengths than tracks going to the bottom row.

The reason is that the topmost row of pins on the rightangled connect have longer leads than the bottom row.

If a PCB mounting rightangled connector is used, track length compensation shall be performed at the connector end of the PCB tracks to maintain the differential signal across the PCB.

Cable assembly

Overview

Cable assemblies consist of two identical plug connectors joined by a length of cable.

Cable length

The maximum length of the cable assembly should be 10 m to ensure that the end to end skew and jitter introduced by the cable assembly does not exceed the maximum budget for the cable.

Longer length cables may be used at slow data signalling rates provided that the signal attenuation (see clause 6) and system jitter and skew limits are not violated at the operating data signalling rate (see clause 6.6.4).

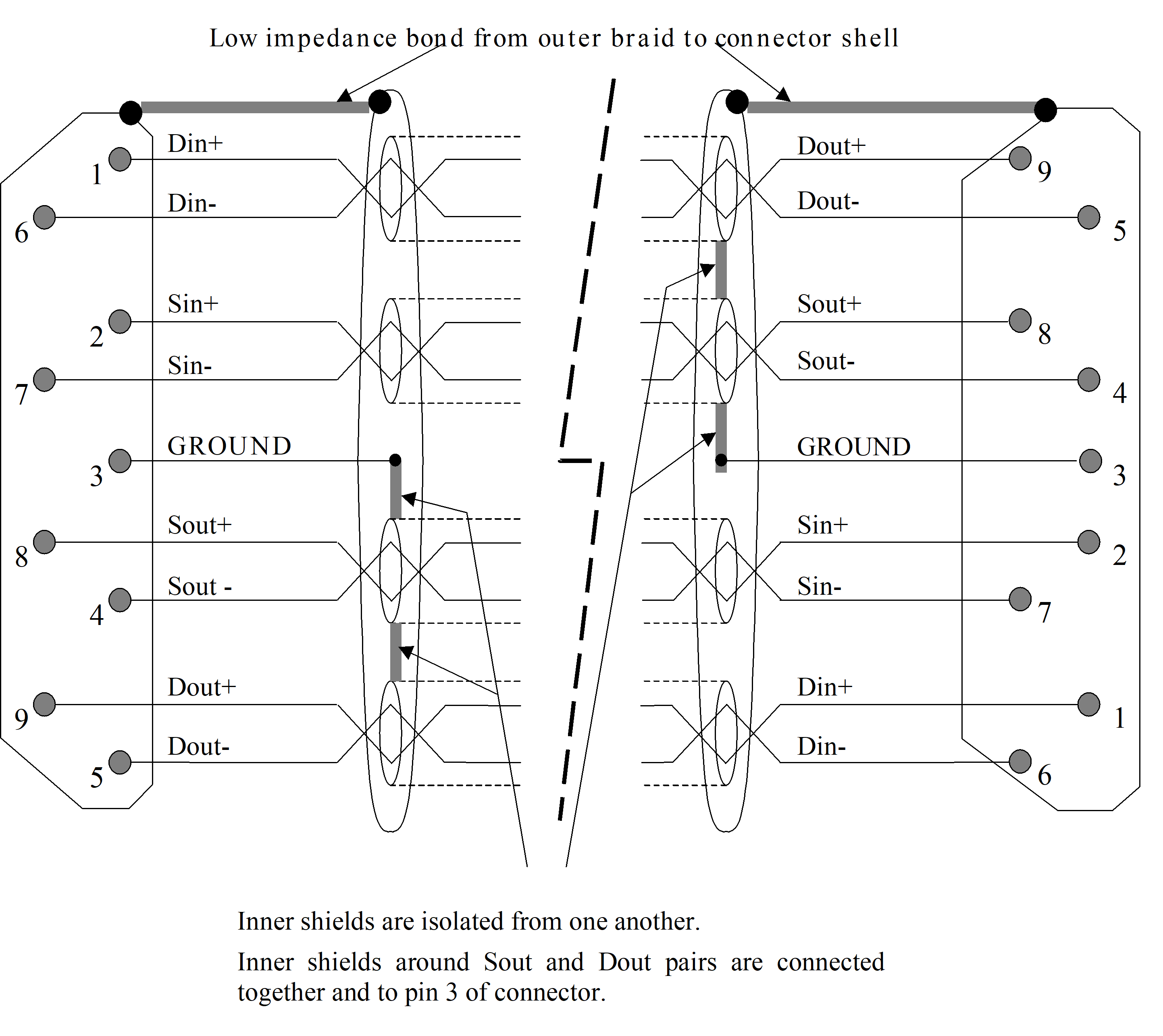

Cable connections

The connector contacts shall be terminated as shown in Figure 53 and Table 53.

The cable signal wires cross over to achieve a transmit to receive interconnection, e.g. Dout+ is connected to Din+ .

The individual shields of the differential signal pairs carrying the output signals Dout+, Dout- and Sout+ and Sout- shall be connected together and to pin 3 of the connector.

The shields are terminated at the end of the cable from which the signals are being driven, following good EMC practice. In this way two of the differential pairs are connected at one end of the cable and the remaining two at the other end. A symmetrical arrangement results, avoiding the problem of having to know which end of the cable is which during installation.

A metal shell shall be used for each connector to provide necessary shielding of the connector.

The outer shield of the cable shall be bonded to the connector shell via a low impedance connection (less than 1 ).

The metal shell shall be bonded to the main body of the connector via a low impedance connection (less than 1 ).

Figure 53: SpaceWire cable assembly

Figure 53: SpaceWire cable assembly

Table 53: Cable assembly signal wire connections

|

Signal at A end

|

Pin at A end

|

|

Pin at B end

|

Signal at B end

|

|

A-Din+

|

1

|

- Connection -

|

9

|

B-Dout+

|

|

A-Din-

|

6

|

- Connection -

|

5

|

B-Dout-

|

|

A-Sin+

|

2

|

- Connection -

|

8

|

B-Sout+

|

|

A-Sin-

|

7

|

- Connection -

|

4

|

B-Sout-

|

|

A- (Drains of pairs 5,9 and 4,8)

|

3

|

- No Connection -

|

3

|

B-(Drains of pairs 5,9 and 4,8)

|

|

A-Sout+

|

8

|

- Connection -

|

2

|

B-Sin+

|

|

A-Sout-

|

4

|

- Connection -

|

7

|

B-Sin-

|

|

A-Dout+

|

9

|

- Connection -

|

1

|

B-Din+

|

|

A-Dout-

|

5

|

- Connection -

|

6

|

B-Din-

|

|

A-Shield

|

Shell

|

- Connection -

|

Shell

|

B-Shield

|

PCB and backplane tracking

General

As well as routing SpaceWire signals through a cable, the signals can also be transmitted across a PCB or along a backplane.

Only point to point connections are supported on a PCB or backplane, not multidrop bus structures. Bus type structures are built from point to point connections between nodes on the backplane.

Differential signal pairs

Differential impedance

Differential pair signals shall run on a pair of close, parallel PCB tracks with a differential impedance of (100 6) .

This differential impedance can be achieved by adjusting the track thickness, width, separation and height above the ground plane.

Difference in track length for a differential pair

To avoid skew between the two parts of the differential signal, the difference in track length between the two signals from a differential pair shall be less than 5 % of the track length and no more than 5 mm.

Difference in track length for Data and Strobe

The skew introduced between the Data and Strobe (D and S) signals shall be minimized as specified here. For PCB tracks, skew is controlled by making the tracks all close to the same length.

The difference in track length between the Data and Strobe signals shall be less than 5 % of the track length and no more than 5 mm.

Signal level (normative)

Low voltage differential signaling (LVDS)

SpaceWire shall use low voltage differential signalling (LVDS) with electrical characteristics as defined in ANSI/TIA/EIA-644.

Failsafe operation of LVDS

When any of the following fault conditions occur, the receiver outputs shall not oscillate and shall be locked to high logic level provided that a noise threshold of 10 mV is not exceeded at the receiver input.

- Driver not powered.

- Driver disabled.

- Driver not connected to receiver.

- Receiver inputs open circuit (i.e. cable or wire in cable disconnected).

- Receiver inputs shorted together.

When the driver is not powered its output should be high impedance i.e. > 100 k.

When the receiver is not powered its input should be high impedance i.e. > 100 k.

Signal coding

Datastrobe (DS)

SpaceWire shall use DataStrobe (DS) encoding.

DS encoding is defined in clause 5.3.5 of IEEE Standard 1355-1995 [1] and also defined in IEEE Standard 1394-1995 [6]. See annex A for details of the differences between this Standard and IEEE Standard 1355-1995 and the reasons for those differences.

The data bit stream to transmit shall be encoded using two signals Data and Strobe as follows.

The Data signal shall follow the data bit stream, i.e. be high when the data bit is 1 and low when the data bit is 0.

The Strobe signal shall change state whenever the Data does not change from one bit to the next.

The DS encoding is illustrated in Figure 61.

Figure 61: DataStrobe (DS) encoding

Simultaneous transition on data and strobe signals

As data corruption following simultaneous transitions on the Data and Strobe lines is expected, the SpaceWire receiver shall be tolerant of simultaneous transitions on the Data and Strobe lines, i.e. the receiver shall not hang up.

When the SpaceWire transmitter is reset it shall be a controlled reset avoiding simultaneous transitions of Data and Strobe signals.

- 1 For example, after stopping transmission the Strobe signal can be reset first, followed by the Data signal.

- 2 Simultaneous transitions on the Data and Strobe lines are not part of the normal operation of SpaceWire. They can occur, however, either when a SpaceWire cable is plugged in while the transmitter is trying to make a connection, or when the LVDS driver or receiver circuits are enabled while the transmitter is trying to make a connection.

Differential DS

SpaceWire shall use low voltage differential signalling (LVDS) for the Data and Strobe signals.

SpaceWire link

A SpaceWire link shall comprise two pairs of differential signals, one pair transmitting the D and S signals in one direction and the other pair transmitting D and S in the opposite direction.

This is a total of eight wires for each bidirectional link.

Data signalling rate

Minimum data signalling rate

The minimum data signalling rate at which a SpaceWire link shall operate is 2 Mb/s.

- 1 The minimum data signalling rate is the lowest data signalling rate at which a SpaceWire link can operate.

- 2 The minimum data signalling rate is set by the disconnect timeout (clause 8.9.2.1 and 8.11.2) to greater than 1,18 Mb/s, i.e. 1/850 ns.

Maximum data signalling rate

The maximum data signalling rate shall be defined.

The maximum data signal rate is the highest data signalling rate at which a SpaceWire link can operate and is defined by consideration of signal skew and jitter (see clause 6.6.4).

Operational data signalling rate

The link in one direction can operate at a different data signalling rate to the same link in the opposite direction.

Links within a system can operate at different data signalling rates.

A SpaceWire link can operate at any data signalling rate between the minimum data signalling rate and the maximum possible data signalling rate.

Effects of skew and jitter

Skew and jitter overview

The maximum data signalling rate that can be achieved is different from one system to another, depending on several factors such as cable length, driverreceiver technology, and encoderdecoder design, and is limited by skew and jitter.

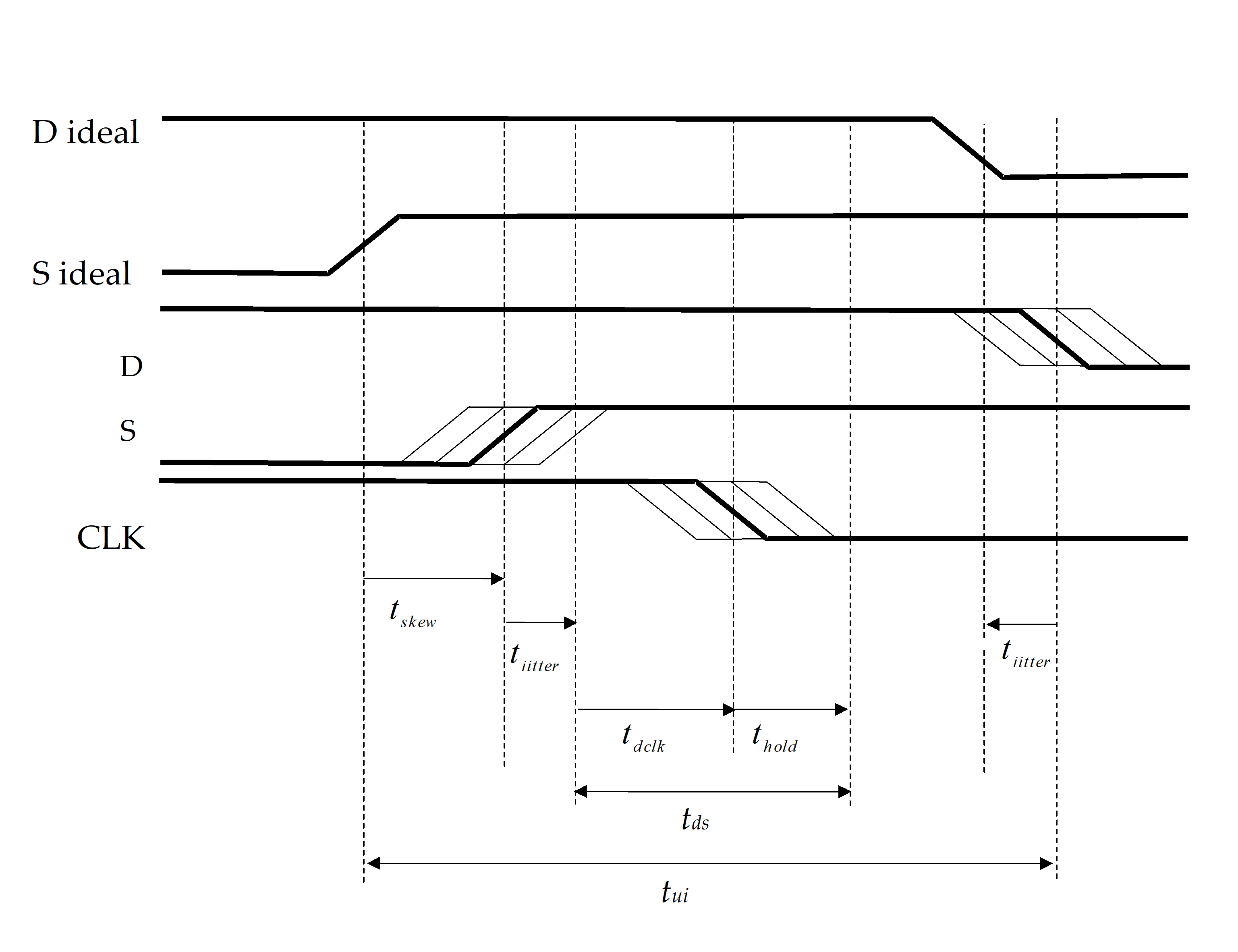

Figure 62 illustrates the effect of skew and jitter on the Data and Strobe signals, where the parameters are as follows:

tskew is the skew between the Data and Strobe signals.

tjitter is the jitter on the Data or Strobe signal. tjitter data = tjitter strobe since they follow identical signal paths (as close as possible).

tdclk is the delay in the receiver from the edge of the Data or Strobe signal, through the XOR operation which produces the clock signal, to the clocking in of the data in the input flipflop. This may be regarded as the setup time for the data input flipflop from the edge of the Data or Strobe signal.

thold is the hold time for the Data signal after the clocking of the data into the input flipflop.

tui is the unit interval or bit period. tui = 1/Fop, where Fop is the link operating data signalling rate.

The tdclk and thold parameters may be combined into a minimum specification for the separation of consecutive edges on the Data and Strobe signals at the input to the decoder, tds = tdclk + thold.

tmargin is the available margin. tmargin = tui – (tskew + 2*tjitter + tdclk + thold).

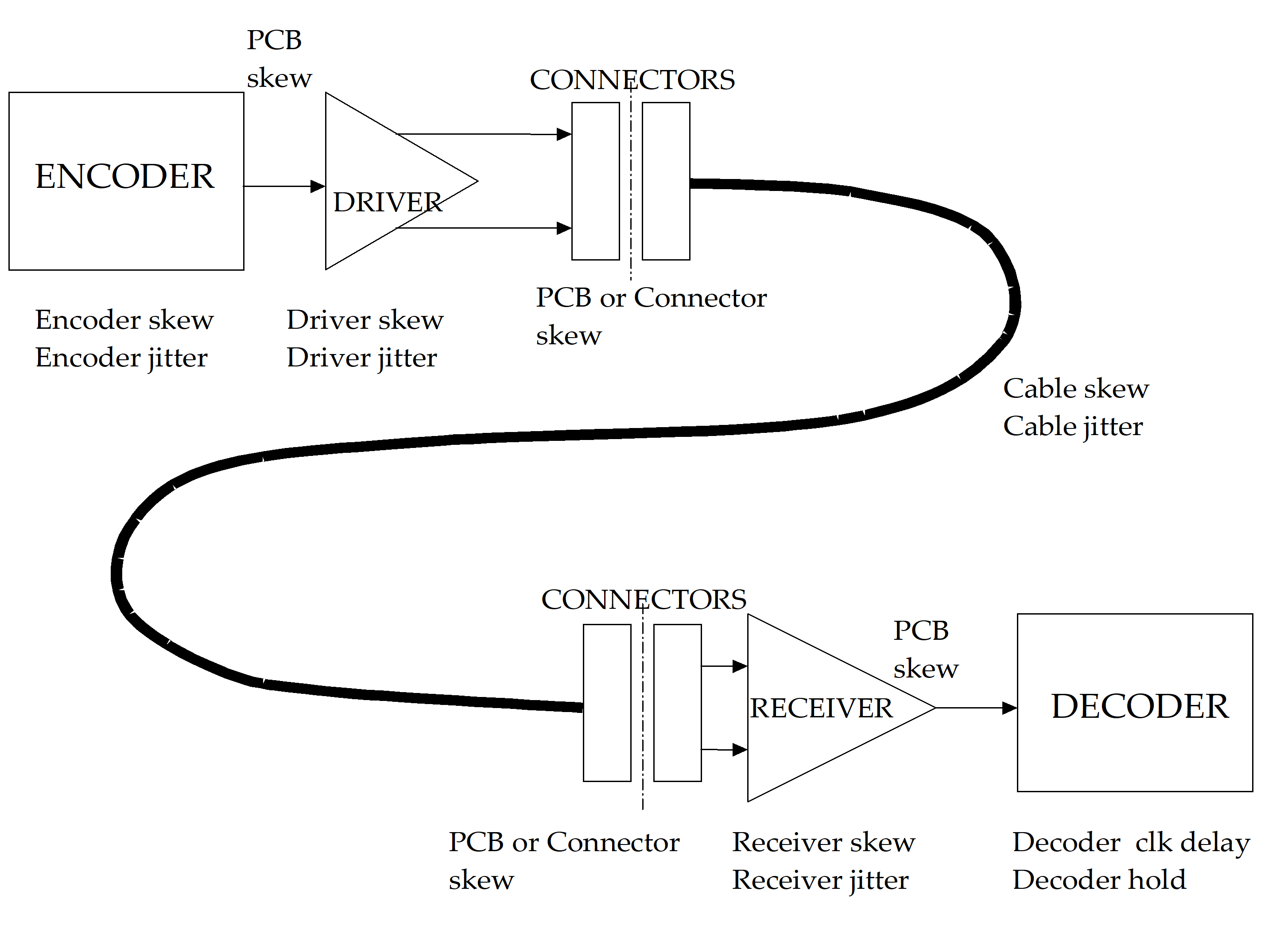

- 1 Figure 63 illustrates the contributors to skew and jitter in a typical system.

- 2 Table 61,

- Table 62 and Table 63 provide the example jitter and skew budgets at three different operating frequencies (100 Mb/s, 200 Mb/s and 400 Mb/s).

- 3 The example jitter and skew figures for 400 Mb/s operation (Table 63) assume that the LVDS driver or receiver are integrated in the same package as the encoderdecoder.

Timing margin

The maximum data signalling rate for a SpaceWire link shall be set so that the timing margin (tmargin) is greater than zero.

Initial operating data signalling rate

After a reset or disconnect (see clause 8.9.2.1) the SpaceWire link transmitter shall initially commence operating at a data signalling rate of (101) Mb/s.

The SpaceWire link transmitter shall operate at (101) Mb/s until commanded to operate at a different data signalling rate.

- 1 The aim is to provide all systems with a common, slow, initial data signalling rate so that system operation can be validated before switching to higher and possibly widely different data signalling rates.

- 2 This initial slow data signalling rate is applicable to all SpaceWire systems, but they need not be capable of higher data signalling rates.

Figure 62: Skew and jitter

Figure 62: Skew and jitter

Figure 63: Contributors to skew and jitter

Figure 63: Contributors to skew and jitter

Table 61: Example jitter and skew budget at 100 Mb/s

|

|

Data jitter

|

Strobe jitter

|

Skew

|

Min edge separation

|

Total

|

|

Encoder skew

|

|

|

0,50

|

|

|

|

Encoder jitter

|

0,50

|

0,50

|

|

|

|

|

PCB skew

|

|

|

0,05

|

|

|

|

Driver skew

|

|

|

1,00

|

|

|

|

Driver jitter

|

0,50

|

0,50

|

|

|

|

|

PCB/connector skew

|

|

|

0,10

|

|

|

|

Total transmitter

|

1,00

|

1,00

|

1,65

|

|

3,65

|

|

Cable jitter |

0,50

|

0,50

|

|

|

|

|

Cable skew

|

|

|

1,00

|

|

|

|

Total cable

|

0,50

|

0,50

|

1,00

|

|

2,00

|

|

PCB/connector skew

|

|

|

0,10

|

|

|

|

Receiver skew

|

|

|

1,50

|

|

|

|

Receiver jitter

|

0,50

|

0,50

|

|

|

|

|

PCB skew

|

|

|

0,05

|

|

|

|

Decoder clock delay and hold

|

|

|

|

1,00

|

|

|

Total receiver

|

0,50

|

0,50

|

1,65

|

1,00

|

3,65

|

|

Total system

|

2,00

|

2,00

|

4,30

|

|

8,30

|

|

Margin

|

|

|

|

|

1,70

|

Table 62: Example jitter and skew budget at 200 Mb/s

|

|

Data jittertjitter (ns)

|

Strobejittertjitter (ns)

|

Skewtskew (ns)

|

Min edge separationtds (ns)

|

Total(ns)

|

|

Encoder skew

|

|

|

0,50

|

|

|

|

Encoder jitter

|

0,10

|

0,10

|

|

|

|

|

PCB skew

|

|

|

0,05

|

|

|

|

Driver skew

|

|

|

0,07

|

|

|

|

Driver jitter

|

0,20

|

0,20

|

|

|

|

|

PCB/connector skew

|

|

|

0,10

|

|

|

|

Total transmitter

|

0,30

|

0,30

|

0,72

|

|

1,32

|

|

Cable jitter

|

0,50

|

0,50

|

|

|

|

|

Cable skew

|

|

|

1,00

|

|

|

|

Total cable

|

0,50

|

0,50

|

1,00

|

|

2,00

|

|

PCB/connector skew

|

|

|

0,10

|

|

|

|

Receiver skew

|

|

|

0,12

|

|

|

|

Receiver jitter

|

0,20

|

0,20

|

|

|

|

|

PCB skew

|

|

|

0,05

|

|

|

|

Decoder clock delay and hold

|

|

|

|

1,00

|

|

|

Total receiver

|

0,20

|

0,20

|

0,27

|

1,00

|

1,67

|

|

Total system

|

1,00

|

1,00

|

1,99

|

1,00

|

4,99

|

|

Margin

|

|

|

|

|

0,01

|

Table 63: Example jitter and skew budgets at 400 Mb/s

|

|

Data jittertjitter (ns)

|

Strobejittertjitter (ns)

|

Skewtskew (ns)

|

Min edge separationtds (ns)

|

Total(ns)

|

|

Encoder skew

|

|

|

0,20

|

|

|

|

Encoder jitter

|

0,10

|

0,10

|

|

|

|

|

PCB/connector skew

|

|

|

0,05

|

|

|

|

Total transmitter

|

0,10

|

0,10

|

0,25

|

|

0,45

|

|

Cable jitter

|

0,35

|

0,35

|

|

|

|

|

Cable skew (5m max. length)

|

|

|

0,50

|

|

|

|

Total cable

|

0,35

|

0,35

|

0,50

|

|

1,20

|

|

PCB/connector skew

|

|

|

0,05

|

|

|

|

Receiver jitter

|

0,10

|

0,10

|

|

|

|

|

Decoder clock delay and hold

|

|

|

|

0,50

|

|

|

Total receiver

|

0,10

|

0,10

|

0,05

|

0,50

|

0,75

|

|

Total system

|

0,55

|

0,55

|

0,80

|

0,50

|

2,40

|

|

Margin

|

|

|

|

|

0,10

|

Altering data signalling rate

The transmitter operating rate shall not be changed before the link connection has been made fully.

I.e. the exchangelevel state machine is in the Run state; see clause 8. Once in the Run state (see clause 8.5) the transmitter operating rate can be set at any rate between the minimum (see clause 6.6.1) and the maximum data signalling rate (see clause 6.6.2).

Character level (normative)

Overview

The character level protocol defined in this clause takes into consideration the DSSE and DSDE character level encoding given in IEEE Standard 1355-1995 [1], but it additionally includes TimeCodes for sending system time information across a SpaceWire link. The host interface to the SpaceWire encoderdecoder is specified.

Data characters

As illustrated in Figure 71, a data character shall contain a parity bit, a datacontrol flag and eight bits of data as follows.

The datacontrol flag shall be set to zero to indicate that the current character is a data character.

The eightbit data value shall be transmitted least significant bit first.

Figure 71: SpaceWire data characters

Control characters and control codes

A control character shall be formed from a parity bit, a datacontrol flag and a twobit control code with the datacontrol flag set to one to indicate that the current character is a control character.

The different control characters are illustrated in Figure 72.

Figure 72: SpaceWire control characters and control codes

Figure 72: SpaceWire control characters and control codes

The NULL control code shall be formed from ESC followed by the flow control token (FCT).

- 1 The parity bit (P) in the middle of the control code is zero, in accordance with clause 7.4b).

- 2 NULL is transmitted whenever a link is not sending data or control tokens, to keep the link active and to support link disconnect detection (see clause 8).

The time control code (TimeCode) shall be formed from ESC followed by a single data character. - 1 The parity bit (P) in the middle of the TimeCode is one, in accordance with clause 7.4b).

- 2 The TimeCode is used to distribute system time information (see clause 8.12) and control flags isochronous with the timecode distribution.

Six bits of time information shall be held in the least significant six bits of the TimeCode (T0T5) and the two most significant bits (T6, T7) shall contain control flags that are distributed isochronously with the TimeCode.

An escape character (ESC) followed by ESC, EOP or EEP is an invalid sequence and shall be noted as an escape error (see clause 8.9.2.3).

Parity for error detection

A parity bit shall be assigned to each data or control character to support the detection of transmission errors.

The parity bit shall cover the previous eight bits of a data character or two bits of a control character, the current parity bit, and the current datacontrol flag.

The parity bit shall be set to produce odd parity so that the total number of 1’s in the field covered is an odd number.

The coverage of the parity bit is illustrated in Figure 73.

Figure 73: Parity coverage

Transmit bit pattern after reset or link error

After reset or link error (while in the ErrorReset state, see clause 8) the Data and Strobe signals shall be set to zero.

When the transmitter is enabled after reset the first bit that is sent shall be a parity bit, this bit shall be set to zero so that the first transition shall be on the Strobe line.

This results in the patterns shown Figure 74 appearing when a link is started.

Figure 74: Data and strobe signals on link start

Host interface to transmitter and receiver

When the transmit and receive data interfaces to the host comprise eight data bits and one control flag, the coding given in Table 71 shall be used.

Thus, for example, any code with the control flag set to one and the least significant bit of the data set to zero represents an EOP. This prevents the transmitter being asked to send an invalid control code.

Table 71: Transmitter and receiver host data interface coding

|

Control flag

|

Data bits (MSB LSB)

|

Meaning

|

|

0

|

xxxxxxxx

|

8bit data

|

|

1

|

xxxxxxx0 (use 00000000)

|

EOP

|

|

1

|

xxxxxxx1 (use 00000001)

|

EEP

|

EEP may be written into the transmitter interface

A SpaceWire node is the source of a packet and does not normally send packets that are in error (indicated by termination with an EEP) so normally there is no need to write EEP into the transmitter interface, unless, for example, some exception occurs in the node during the transmission of a packet. As specified in clause 10.5.3, a SpaceWire Router forwards packets where an error has occurred (i.e. packets that are terminated by an EEP) so in the case of a router any EEP is written into the transmitter interface.

For the two control codes (EOP and EEP), Since only the least significant bit is decoded, the following bits should be set:

- when writing to the transmit interface, set to zero the remaining data bits.

- when receiving, set the seven most significant data bits to zero when the control bit is set.

Time interface

The time interface to the host system shall comprise two signals, TICK_IN and TICK_OUT, a sixbit time output port, a sixbit time input port, a twobit control flag input port and a twobit control flag output port.

When TICK_IN is asserted and the link interface is in the Run state (see clause 8.5) it shall cause the transmitter to send a TimeCode immediately after the current character has been transmitted.

TICK_OUT shall be asserted whenever the link interface is in the Run state and the receiver receives a valid TimeCode.

Only one node in a SpaceWire network should have an active TICK_IN signal.

All other nodes should keep the TICK_IN signal not asserted.

The node with the active TICK_IN signal provides the master time reference for the entire SpaceWire network.

A sixbit time output shall be provided from the link receiver to the local time counter.

The other two bits of the time output are the two controlflag outputs and are reserved for future use.

A sixbit time input shall be provided to the link transmitter from the local time counter.

The other two bits of the time input are the two controlflag inputs and are reserved for future use.

The two control flags are reserved for future use and shall both be set to zero.

Exchange level (normative)

Overview

The exchange level protocol takes into consideration the DSSE and DSDE exchange level protocol given in clause 5.7 of the IEEE Standard 1355-1995 [1], but it also includes additional features in the state machine in order to eliminate problems with the ResetLinkCommand and several ambiguities within the IEEE Standard 1355-1995 have been resolved. See annex A for details of the differences between SpaceWire and IEEE Standard 1355-1995 and the reasons for those differences.

The exchange level is responsible for making a connection across a link and for managing the flow of data across the link.

Linkcharacters and normalcharacters (normative)

Definitions

At the exchange level, data and control characters are separated into two types: linkcharacters (LChar) and normalcharacters (NChar).

LChars are those that are used in the exchange level and which are not passed on to the packet level. The flow control token (FCT) character and escape (ESC) character are LChars. The NULL control code (ESC + FCT) and the TimeCode (ESC + data character) are escape sequences and may be regarded as LChars. They are not passed on to the packet level.

NChars are the characters that are passed on to the packet level: data characters and endofpacket markers (EOP and EEP).

Actions

Only NChars shall be passed from the host interface to the link for transmission.

The link interleaves LChars and NChars during transmission, but passes only NChars on to the host interface on the receiving side.

A received character shall not be acted upon until its parity has been checked.

Flow control (normative)

To avoid host receive buffer overflow and subsequent loss of data, data flow across a link shall be controlled using flow control tokens sent from one end of the link (end A) to the other end (end B) to signify that end A is ready to receive some more data.

The FCT (flow control token) is defined in clause 7.3.

A FCT sent out by a link interface shall be used to indicate that there is space for eight more NChars in the host receive buffer.

For each FCT sent the host system shall reserve room in its receive buffer to accommodate eight NChars.

The receive buffer is typically a FIFO memory.

The transmitter shall not transmit any NChars until it has received one or more FCTs to indicate that the receiver is ready.

The transmitter shall keep a credit count of the number of NChars that it has been authorized to send, as follows:

- Each time a link interface receives an FCT its transmitter increments the credit count by eight.

- Whenever the transmitter sends an NChar it decrements the credit count by one.

If the credit count reaches zero the transmitter shall cease sending NChars until it receives another FCT increasing the credit count again to eight.

When the credit count is zero the transmitter shall continue to send LChars.

In state ErrorReset the credit count shall be set to zero.

If an FCT is received when the credit count is at or close to its maximum value (i.e. within eight of the maximum value) then the credit count shall not be incremented and a credit error shall be flagged (see clause 8.5.3.6 and 8.9.2.4).

The credit counter shall hold a maximum credit count of 56 (i.e. seven FCTs).

On reset (or after a link disconnect) the initial number of FCTs to transmit shall be set according to the size of the receive buffer (one FCT for every eight NChars that can be held in the receive buffer) up to a maximum of seven.

If the receive buffer has a capacity of more than 56 (seven FCTs worth) then the number of FCTs to transmit initially shall be set to seven. A maximum of seven FCTs can be outstanding at any time.

A link interface shall keep a count of the number of outstanding NChars it expects to receive, i.e. the number it has asked for by sending FCTs, as follows:

- Increment this outstanding count by eight each time an FCT is transmitted

- Decremented this outstanding count by one each time an NChar is received.

After a link reset or after a link disconnect, the initial value of the outstanding count shall be zero.

The outstanding counter shall contain a maximum count of 56, corresponding to seven FCTs.

An FCT shall not be transmitted unless there is room in the outstanding counter to record eight more outstanding NChars and there is room in the receive buffer to reserve space for those eight more NChars (see clause 8.4.8).

When transmission of a TimeCode or an FCT is requested then it shall be sent immediately, as soon as the transmitter has finished sending the current character (or NULL or TimeCode).

When no TimeCode or FCT is requested and NChars are available from the host interface and the flow control credit count is above zero, the transmitter shall send NChars.

If no TimeCode, FCT or NChar are sent, then the transmitter shall send NULL to indicate that the link is still active (and to prevent the disconnect detection mechanism from being triggered at the other end of the link).

The order of priority for transmission of characters shall be as follows: - TimeCode, highest priority;

- FCTs;

- NChars;

- NULL, lowest priority.

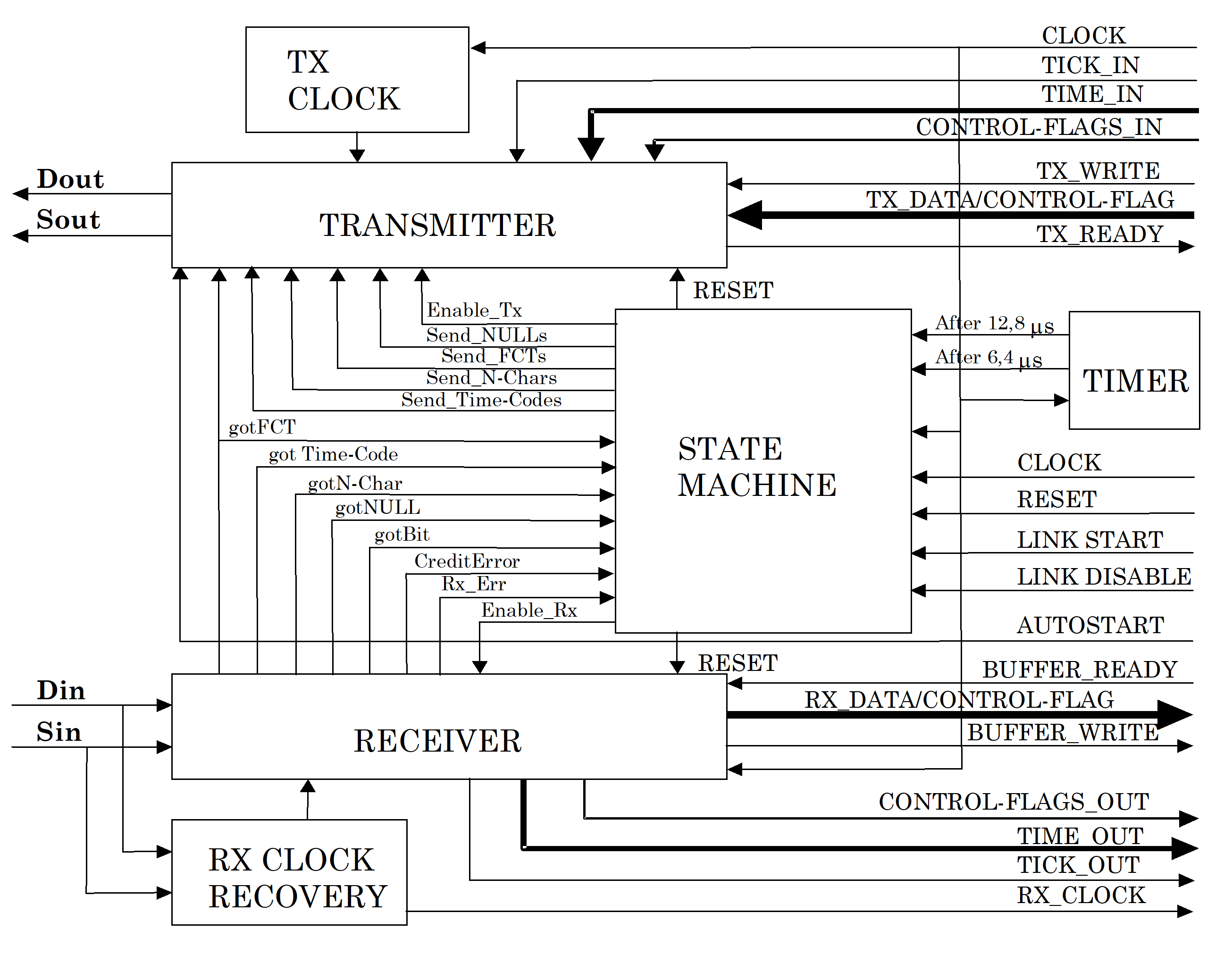

Encoderdecoder block diagram

Overview

An example block diagram of a SpaceWire encoderdecoder is illustrated in Figure 81.

Figure 81: Example SpaceWire link interface block diagram

Figure 81: Example SpaceWire link interface block diagram

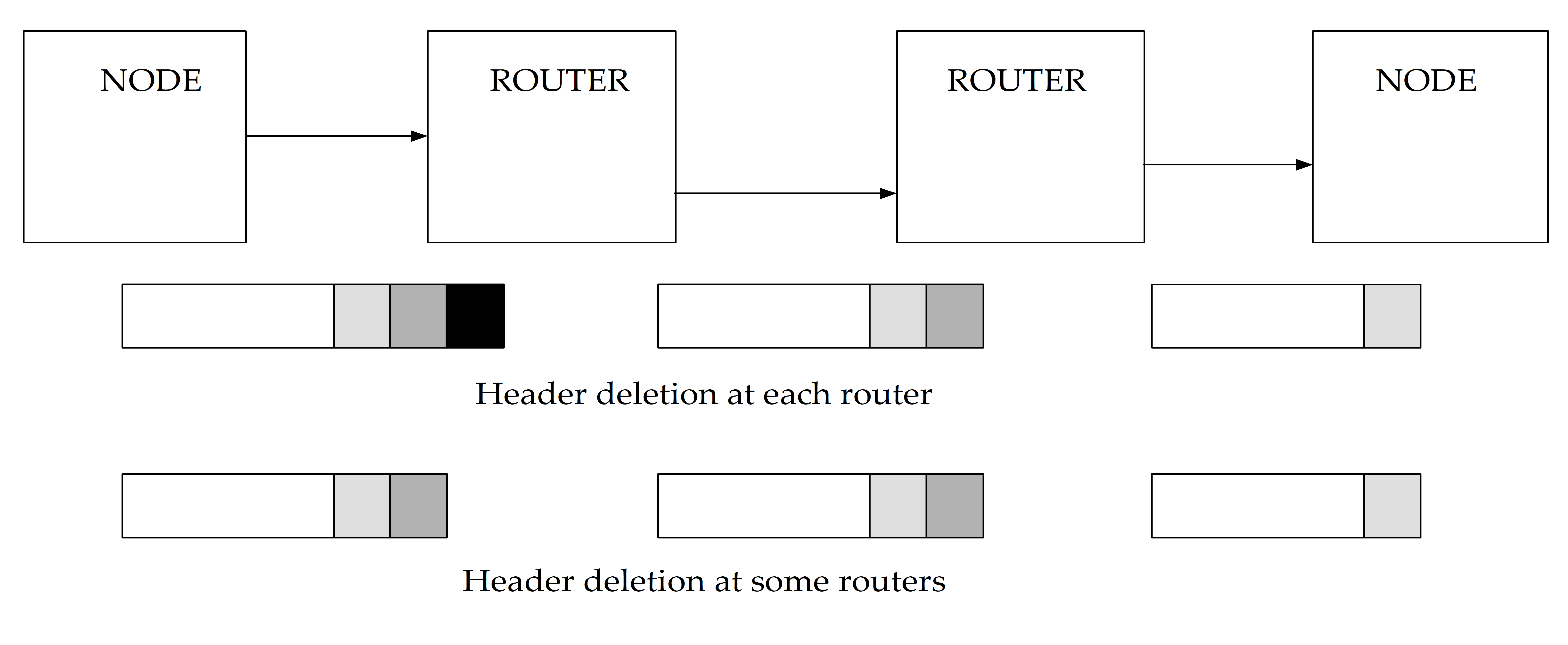

Transmitter